|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

And the result?

Every comic fan knows what happened in the 1990s: Marvel was sold to Ron Perelman, and all he wanted was short term profit. So prices went up, Marvel was told to sell more comics, and after a brief investment bubble sales collapsed and Marvel went bankrupt. Almost the same thing happened in 1968, when Marvel was sold to Martin S. Ackerman,

"a flamboyant ...lawyer and businessman whose career was in mergers, acquisitions, financial workouts and banking. Business Week magazine described him as 'a razzle-dazzle financial operator. In 1968 he became president of Curtis Publishing by lending $5 million through the Perfect Film and Chemical Corporation, a conglomerate that he had built.'" (source)

Ackerman then famously halved the circulation of the Ladies Home Journal, a magazine started by Benjamin Franklin, and selling six million copies. After gutting it he sold it, and it closed down. We don't know exactly what he did at Marvel, but 1968 looks eerily familiar to Ron Perelman's early 1990s:

Ackerman then quit Curtis and Perfect Film in 1969.

The dates may at first look like a coincidence: the Marvel Explosion happened a few months before the company was sold. But look closer: it's no coincidence.

"What happened was

that in late '67, Goodman finally won a major point in his ongoing

battle with Independent. He wanted to publish more comics than

they'd allow him to put out, and he wanted to do things like ghost

comics and love comics, which they were then denying him. Finally,

he said to them, in effect, 'Look...my contract with you is

expiring in March of 1969. At that point, you're either going to

let me publish what I want or I'm going to find a distributor who

will. You and I are both trying to sell our companies so we have a

mutual interest in inflating our grosses. Let me expand now and it

will give both companies a big boost.' Jack Liebowitz, who ran DC

and Independent, had previously been worried about allowing

Goodman to flood the newsstands with product, fearing it would

harm the market and harm DC. But he was then angling to sell DC

and Independent to a company called Kinney National Services, and

he saw the wisdom of even a temporary jolt to the distributor's

fortunes. He also knew that Goodman wasn't bluffing; that he could

find a distributor who would let him publish without restriction.

Liebowitz wanted to keep Marvel under the Independent umbrella if

that was at all possible, so they negotiated a new arrangement. It

didn't lift all restrictions right away but it did allow him

considerable expansion room, which he used to begin adding more

titles."

"Goodman had plans

for Marvel to expand as far back as 1965. He felt he could

convince Jack Liebowitz at DC to distribute more of his titles

because Marvel’s sales were soaring. Martin was determined to add

more superhero titles to his lineup as soon as possible. At

several points in 1966 and 1967, Goodman thought he was on the

verge of convincing Independent News to expand his line. One week

he’d tell Stan it was on, the next week no dice." - Mark

Alexander, "Lee & Kirby: The Wonder Years"

The ever changing, ever developing universe stopped in its

tracks. Regarding late 1968, Sean Howe writes: "For the last year or two, Lee had

conveyed to his writers that Marvel's stories should have only

'the illusion of change,' that the characters should never

evolve too much, lest their portrayals conflict with what licensees had planned for other

media." -"Marvel Comics: The Untold Story" p.101

Up until 1968, sales increased year after year. After 1968, sales declined year after year.

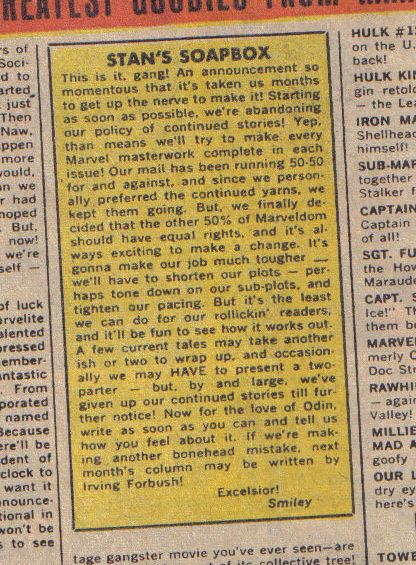

"Roy Thomas: In 1968 Marvel expanded. Every super-hero had his own

title - Iron Man, Sub-mariner, Captain America.

"Stan Lee: I was drunk with

power.

"Roy Thomas: And soon after

that, there was a downturn in sales in general. Do you think

there was an over-expansion?

"Stan Lee: ...They go up, they

go down. It's hard for me to remember specifically any

particular event or why it happened."

- from Comic Book Artist Collection by Job B Cooke, Neal Adams,

page 112

The "industry trends" theory

A common explanation for the reducing sales in 1968 is that all

comics were losing readers at the time. But there had been a

steady decline since the late 1940s: the 1960s was no different.

Between 1961 and 1967 Marvel proved that all you need to buck the

trend is realism and amazing stories. In 1968 Marvel changed

dramatically, asking readers for more and giving less in return.

Is it a coincidence that Marvel sales then fell?

The "unrepeatable luck" theory

Marvel has been milking these brands for so long that it's come to

look back on the 1960s as a fluke, as unrepeatable luck. But as

Jack Kirby said, this was not luck, it was hard work and a passion for realism. Marvel can

repeat this luck any time it wants: every time Marvel has tried

realism, sales have gone up and

new iconic brands created.

Merchandising began to grow in 1966 and 1967, and by 1968 Marvel could see its attraction: licensing deals are one hundred percent guaranteed no-risk profit! Today Marvel is almost entirely a brand management company with only a small percentage of its money coming from comics. The comics exist to serve the brands, and so character development - the basis of a realistic story - is against Marvel's short and medium term financial interests.

The Marvel Explosion saw 8 books increased to 12. Soon after, the 12c price increased to 15c. The price of being a dedicated Marvel fan almost doubled, from 96c to $1.80. This may not seem a big deal, but since time immemorial, comics had been cheap. For more than a quarter century, including the entire golden age, comics had been a dime. For the silver age, comics were 12c. That 20% price increase was still resented, and helped destroy the biggest selling comic of the 1950s. Now a further 25% price increase, soon to be followed by an additional 33% price increase to 20c, meant the whole foundation of comics - good value for money - was being undermined.

"Why does price matter? I though only realism mattered?"

The value of comics is increased by realism and excitement (see the formula given in FF9.) That value

is measured in dollars and cents. A comic that may be great value

for 12c may be poor value at 15c. It's not rocket science.

Not only did comics cost more, but you got less for your money on each page:

"By the late ‘60s, Kirby had largely switched over to a looser, more action-oriented style, incorporating more full-page panels and three- to four-panel pages. Rumor has it he asked for a raise, was refused, and Stan told him to draw fewer panels instead. Another possible factor: In the mid-‘60s, the American comics industry switched to a smaller standard original art size. Before, artists had usually drawn at roughly twice printed size; the new standard was only about 1 1/2 times printed size. This led to less detailed pages but encouraged a more intimate look -- and fewer panels. ... Stan Lee printed a few complaints about this change of pace -- or, rather, pacing -- in the FF letter columns of the time. But for the most part, fans liked it because Kirby’s storytelling abilities were at their peak." - from "A THOUSAND FLOWERS: Comics, Pop Culture, and the World Outside," Installment 27, by Stuart Moore, 09-23-2003 on Newsarama.com

Perhaps the most famous example of this, often referred to at the time by Stan Lee, is where Gene Colan took an entire page to show a hand on a doorknob. It was beautiful picture - Colan is a stunning artist, the best Marvel had, by a long way, if space was not an issue. But space was an issue, and this meant less story for the customer.

With less on each page, more stories had to stretch out. Fans noticed and they complained. Stan defended himself on the splash page of FF61, and later promised to stop all multi part stories. But multi part stories were never the problem. Fans love multi part stories, as long as each book gives value for money, and Stan was forced to bring them back. What fans hate is stretched out stories, where you pay for "a book length bombshell" but only get a chapter.

After 1967 the best talent was spread ever thinner. This is often the case in later years as well: fewer titles means higher quality. Take Spider-Man for example:

It's no surprise that 1968 saw a nosedive in quality. Tom Brevoort recalls one story:

When Marvel had only eight comics it was easy for one person (e.g. Stan) to be intimately involved in them all. You got a feeling that each story really mattered, and the shared Marvel Universe was naturally seamless. With more books, more details were forgotten or ignored.

"Roy Thomas: Everyone's heard tales

of you physically playing out stories, jumping on tables, and

acting out 'Thor' stories.

Stan Lee: I used to enjoy

doing that. ... writing at the typewriter, hour after hour, got

kind of boring. I would do whatever I could to jazz it up."

-Comic Book Artist Collection by Job B Cooke, Neal Adams,

page 111

With more comics, Stan took more time at editing and managing

and less time at the typewriter. So he didn't know the stories as

closely and never needed to act them out. With so many more

stories to cover, Stan wasn't even aware of what was happening in

each comic any more. The late 1960s Fantastic Four for example

were almost one hundred percent plotted by Jack Kirby, and Stan

just added dialog. The results could be amazing, but only if you

had the world's greatest comic creator on the job. Then Jack left.

Jack Kirby didn't just produce fewer ideas, he physically moved

from New York to the other side of the country (California). So

there were no more visits with Stan.

The Ackerman buy out meant the marvel staff was treated shabbily.

Flo Steinberg quit when they would not raise her hourly wage.

Instead of the promised royalties, Kirby was given a loan, and

told to pay it back at 6% interest. Roy Thomas added a day to his

vacation to get married, and was punished by having his title

taken away from him. See "Marvel Comics: The Untold Story" by Sean

Howe, p. 93.

Steve Ditko had left in 1966, partly over not being rewarded, and partly over his refusal to compromise with the realism of Spider-man. For Jack Kirby, he stopped creating major new characters after November 1967. The last straw was the dumbing down of the "Him" story in Fantastic Four 66. The always excellent TwoMorrows.com gives the details, and concludes with the significance to the change (dates emphasized):

"Lest anyone doubt the creative input from Kirby, from November '65 to November '67 —two years where Jack was pretty much doing the stories on his own, plus plotting for other books that he wasn't drawing—from the imagination of this man came:

"Black Bolt, Gorgon, Crystal, Triton, Karnak, Lockjaw, Galactus, The Silver Surfer, Wyatt Wingfoot, The Black Panther, Klaw, Sub-Space (later dubbed The Negative Zone), Blastaar, The Sentry, The Supreme Intelligence, The Kree, Ronan, Him, Psycho-Man, Hercules, Pluto, Zeus and the Greek Pantheon, Tana Nile and The Space Colonizers, The Black Galaxy, Ego the Bioverse, The High Evolutionary, Wundagore and The New-Men, The Man-Beast, Ulik, Orikal, The Growing Man, Replicus, The Enchanters, The Three Sleepers, Batroc, A.I.M., The Cosmic Cube, The Adaptoid (who later becomes The Super- Adaptoid), Modok, Mentallo, The Fixer, The Demon Druid, The Sentinels, and The Mimic. This is not complete as secondary creations such as The Seeker, Prester John, The Tumbler and others weren't mentioned; but they all premiered within the two-year period.

"After November '67, for the last three years that Jack worked for Marvel, you get the exact opposite; many secondary characters, but very few memorable ones. In FF, the only character of note after November '67 is Annihilus. In Thor you have Mangog and possibly The Wrecker. In Cap you could consider Dr. Faustus and The Exiles. Jack does some good work with some of the classic characters like Dr. Doom, the Mole Man, and Galactus among others. Even the "Him" character is brought back in Thor #165 and 166 in a pretty standard Kirby slugfest. (It's interesting to note that throughout the story, Jack refers to the character as "Cocoon Man"; perhaps Jack objected to the "Him" name?) In any event it's pretty obvious where "The House of Ideas" got their "ideas" from; but now the "house" was being put under creative foreclosure; in fact towards the end, Jack was asking Stan to come up with "ideas" for the stories, which is why you have characters like The Monocle, the Crypto-Man, and a retread of The Creature from the Black Lagoon in the last few Lee/Kirby issues."

Some fans say that that

Evanier exaggerated, and Kirby did not care if his stories were changed,

and neither would be stockpile ideas to impress his next employer. The reader can decide. I just report what I read.

Incidentally, Jack got no more respect when he returned in the 1970s. As "Jason" recalls

As for the 1980s, we all know about his battle to get his original art back (though much of which was lost, stolen by people who wandered through the Marvel offices). Of course, now that he is dead, Kirby is treated like God (literally, in Waid's run on the Fantastic Four). But anyway, back to 1968.

The Marvel Explosion, and the loss of Ditko and Kirby, meant new talent had to be brought in. The new talent fulfilled the corporate need: to milk the brands. To keep writing the same kinds of stories . They had no reason to want new ideas.

Roy Thomas: Most of the new writing was by Roy Thomas. But he was a fan who came straight from school (except for a fewer months as an English teacher). He was, and still is a great guy, a real fan's fan, but he lacked experience.

John Buscema: John Buscema was a great artist, but didn't care at all about superheroes. He was the last person in Earth to be passionate about making them believable.

"I'm not interested in any super-heroes. Some of the Conan books I enjoyed. I'm sorry I didn't ink more of them, but at the time I wasn't interested. All I was interested in was how much I could make today. .. Anything with super-heroes, I'm not interested." (source)

John Romita: John Romita was another great artist, but had no interest in new ideas. His Spider-Man looked much classier than Ditko's, but had less realism.

"It had become very hard for me to come up with new ideas.... So I said, 'If I do any comics ... I'll do inking only...." (source)

Gil Kane: Gil Kane was another great artist who lacked any interest in plots. His art did have a good realistic edge, but he was so good that Stan kept him mainly on covers, so we never saw a consistent Gil Kane influenced story.

Gerry Conway explains: "after doing a few stories with him in my usual loosely plotted style, I began giving him tighter plots, indicating where the story had to be by such-and-such a page. He seemed to prefer this." (source)

Gene Colan: Colan was perhaps Marvel's best artist, when space was not an issue, but like Buscema he wasn't that interested in the plot or in superheroes generally.

"Colan would from time to time rewrite plot points so that they were easier to draw. Colan made no secret of his preference to work on horror titles." (source)

Creative geniuses are rare but they do appear every few years. Once such was Jim Steranko. When modern fans look back at ground breaking comics that still bring gasps of amazement, they remember Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, and Jim Steranko. Jim appeared at just the right time: hitting his stride in 1968 as the others were leaving. Like Ditko, Steranko refused to compromise his vision, and so he was driven away. (Details; more details.) In the interests of balance, it should be noted that Steranko's work was often late. And why was that? Just look at his pages: he put in far more work than he was paid for. If an artist does work for nothing and drives fans wild with excitement, you don't fire him! You thank your lucky stars and find some other artist to draw filler issues.

Like Kirby and Ditko, Steranko held (and holds) passionate views of honor and truth. Like Kirby he was a fighter with a wealth of experience and interests to draw from. He provided "incredible exploits and down to Earth realism" that amazed and attracted fans, but that apparently wasn't enough. Marvel was only interested in milking old brands. New ideas were not a high priority.

"Steranko had realism? Really?"

We may not associate Steranko with realism, but go back and look

at his comics. Steranko's super powered people were good,

but nothing special. But his ordinary people have never been

equaled: Captain America, Nick Fury, his horror and romance

comics, etc. And read the stories - like the Shield issue that's

based on an actual UFO sighting and power cut in New York, or the

use of photos: everything he did seemed hyper-real.

The best writers are driven away whenever they appear

Time and again over the next decades the best writers are driven

away by frustration at Marvel's fear of change. Steve Gerber,

Steve Englehart, Alan Moore, etc., they all left and speak bluntly

about Marvel's hatred of creativity.

Regarding the winter of 1967/1968:

"No one could have known it at the time, but the first flush of

the Marvel Age was coming to an end. That winter, leaving a

Christmas party, Stan Lee jumped up and clicked his heels in the

air - and then fell, breaking his ankle. He spent the last weeks

of 1967 in bed." - "Marvel Comics: The Untold Story" by Sean Howe,

p.87

The glory days of Marvel and DC are often referred to as the Silver Age. How and when did the Silver Age end? Comicartville points to "the sea-change in content that occurred in 1968"

Other fans say it was when Kirby left, but as has been shown, he started withholding his best ideas in 1968. The real experts are the people behind the Silver Age Marvel Comics Cover Index (SAMCCI). The SAMCCI Reviews Section offers an in-depth analysis, issue by issue, of Silver Age Marvel. The era is divided into four parts: (1) The Early, Formative Years, (2) The Years of Consolidation, (3) The Grandiose Years, and (4) The Twilight Years. So here's the sixty four thousand dollar question, when did the Silver Age end?

"Despite the temptation to use Jack Kirby's departure from the company as marking the end of the Grandiose Years, the fact is, no era can be demarcated by a single event. In fact, it's the contention here that Marvel's exit from the Silver Age began almost two full years before Kirby left."

"Almost two full years before Kirby left" takes us to the changes of 1968. This is what changed, according to the SAMCCI review, and the common thread (not identified by SAMCCI) is Marvel Time.

1. Less interest from writers. The new generation of writers and artists "steered their most creative energies away from the books that had become the bedrock of the line." Note that Marvel Time limits what a writer can do. So naturally writers feel limited by these books.

2. Reusing ideas. "Elements such as characterization and realism began to fade and humor became stale; formula trumped originality." See the SAMCCI reviews of FF 84, 85 and 87 for examples. Note that the whole purpose of Marvel Time is ti extend stories well beyond their natural life.

3. Less care over continuity. "There was some internal consistency with past events, but little reference to the wider Marvel Universe" with stories "Riddled with more inconsistencies than readers this late in the silver age could be expected to swallow without abandoning their suspension of disbelief." Note that Marvel Time is designed to let writers write the same kind of stories with the same characters again and again. This only works if you don't pay much attention to the last time a character did the same thing.

4. Loss of institutional memory. The authors refer to "the eventual loss of the institutional memory of the industry's older professionals." The older professionals remember a time when superheroes did not dominate, when there was no fan base, when they had to constantly change to attract new readers. Note that Marvel Time reduces creativity: you do the same kind of stories again and again.

5. The end of optimism. "The high-flown, optimistic language of Stan Lee that not only captured the spirit of the 1960s, but caught the imagination of a generation of readers coupled by the soaring visions of Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, Don Heck, Jim Steranko, John Buscema & Gene Colan, had all but vanished by the mid-1970s."

"I was there, sort of, when Gwen Stacy died. But I had mentally started to check out of comics well before then. I think it began to die for me just as Marvel expanded the line in 1968. There were so many additional books, that the classic creators seemed to get lost in the flood. Kirby was about to leave in only two more years, the Avengers were being written by someone new, and the artwork had changed on almost every single book. Gene Colan, who brought such realism to Iron Man in Tales of Suspense, and then Daredevil, had moved on to (gulp) Dracula. The things that brought this home for me, was the dreadful redesign of the marvel comics covers, to be a frame, and the return of word balloons on the covers. Perfect example: Marvel Two in One, or Marvel Team-Up. Submariner seemed to lose its direction, just as Daredevil also was wandering. Kirby had left Thor, and his last year on both FF and Thor were marked with single issue, small panel stories where his heart just wasn't in it.

Spidey had sprouted four extra arms, and gone to the savage land and back, dealt with a (gulp) vampire by another name "Morbius", and prices of comics had fluctuated up and down, jumping from 15 cents to 20 or 25 and back down again. It was hard to predict how much a book was going to cost. At one point, Daredevil and Iron Man were supposed to be combined, but it didn't happen. The Inhumans had not only finally gotten their own book, but the art and story were terrible, without Kirby at the helm. Even the first four 10 page installments, though drawn by Kirby, were inked heavily by Chic Stone, and looked even more cartoony. And then gears were shifted, and we got a very realistic Neal Adams four part arc, and then it went to hell and was dropped. Everything in marvel seemed to rush towards vampires, werewolves, living monsters and mummies. But the thing that I detest, and remember the most is those stupid frames on the cover of every marvel book.

So, when it came to ASM 121, I wasn't really buying comics anymore, but had moved on to other interests, and left comics behind. I had walked into the bookstore or to the newsstand, and I saw that Spidey was holding a limp Gwen in his arms, but I didn't care, cause I knew it was just a gimmick just as the four arms had been. Only two issues before, the Hulk had shown up for just a single issue... and the same stunt had been used as the last issue of the X-men showed up in #66. But the quality of the stories had fallen, and the wonder and excitement over the drama was gone.

It was time for new writers, new ideas, and new directions to take center stage, but I wouldn't be around for it. As a result, it would be almost 8 years until I would pick up a book and discover the wonder of John Byrne's art and co-plotting on X-men... Frank Miller's Daredevil and more.

So, I was there when Gwen died, but I no longer cared. It wasn't real to me."

Commenting on this quote, Kirk stresses he was an older fan who was struggling to stay interested in high school when no one else would admit to still reading comics, and then went off to college. It wasn't until AFTER college when he was on his own that he picked up X-men #141 and Daredevil #159 and got hooked again.

Marvel did not die in 1968. The next few decades included many great and memorable stories, including many excellent near-real-time stories. But Marvel Time crippled the ability to create realistic stories. The Marvel Universe stretched thinner and thinner and eventually snapped in 1991. But it was great while it lasted.

In conclusion, Marvel ceased to be the house of ideas, and became a brand management company. They literally sold out in 1968. Which was the year I was born. Not that I'm bitter or anything. :)