|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"My stories were true. They involved living people, and they involved myself. They involved whatever I knew. I never lied to my readers."

"I saw my villains not as villains. I knew villains had to come from somewhere and they came from people. My villains were people that developed problems."

"Y'know, for comics to be effective they have to mirror life in some way. You've got to make them high drama. You gotta make them - not fictional, but you've got to dramatize, like what you see in Captain America."

"If you analyze them, you'll find that I'm not really fictionalizing. There's a realistic ending, there are realistic circumstances, there are realistic beginnings and consequences"

(- Jack Kirby)This realism extends to every detail::

"...Reed and Sue's casual clothes on page 2 and the Thing's

sweater on

page 8, and Sue taking the baby from Crystal on page 2. These

seemingly

minor details make the FF seem like real people, and were a big

part of

the sense of family fans felt reading the comics of the

Lee/Kirby era.

The

very lack of this type of storytelling detail is one of the

reasons the

FF has never reached the heights it attained while Kirby was on

it."

- John Morrow,

introduction to "Fantastic Four: the Lost Adventure"

This is what inspired the best of the next generation:

"What

Kirby offered to me as a reader was both his tremendous visual

imagination and his ability to integrate

incredible super heroics into the most quotidian of urban

settings.

[...] Favorite moments include Thor climbing into a taxi cab and

chatting

with the driver, and Jack spending a half page showing normal

folk on

the street cops, kids, etc.—reacting to Galactus on top of

the Baxter

Building. His world was very much our world, and his superheroes

were

very much a part of it."

(-

Chris

Claremont)

For more about the problem of unrealistic superheroes, see the discussion of power inflation, below. The driving force behind Ditko's storytelling was his desire to be true to a standard. In his interview he speaks about this at great length. For example:

"The biggest thing influencing my style would be that I see things in a certain way and that means handling everything so that personal point of view comes across. ... [every man must constantly] struggle to keep his mind from being corrupted and being ruled by irrational premises. ... The Question and Mr. A are men who choose to know what is right and act accordingly at all times. Everyone should." (ibid)Note that Ditko had no problem with science fiction elements, but in every other way a story had to be true to reality. This appears to be why Ditko eventually left Marvel:

"Comic book historian, Greg Theakston has theorized that Ditko saw Spider-Man as a semi-autobiographical piece, and that Ditko had personal ties to the character. In fact, one can draw a great deal of similarities between Ditko and Peter Parker. Ditko was a shy and mild-mannered student, who wore glasses and was very smart. He was not the most popular student in school, and often kept to himself— sound familiar? According to Theakston, whenever Stan tried to inject any changes into the strip or change the direction of the stories, Ditko felt slighted, crushed. This was in a round about way, about him— his views, his feelings. Ditko was not going to be told how to handle a character he created and molded after his own life and views."

"It was important that Lee's heroes lived in the real world, and not in Gotham City or Metropolis, because they were real people. That is, Marvel Comics imagined how real people might act if they suddenly gained superpowers -- confused, conflicted and not necessarily eager for the responsibility. They were a departure from that straight-arrow hero of the Golden Age, Superman. The next age belonged to Marvel. And Stan Lee ushered it in with his creations."

This is from a CNET business network article:

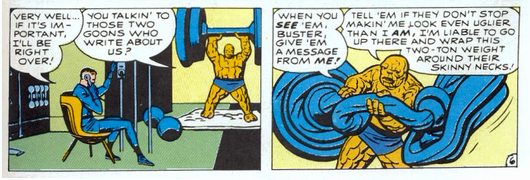

"When Lee's heroes are not defending the earth from weird menaces, however, they lead lives much like other New Yorkers (Lee's stories were set in the real world, not fictional cities such as Metropolis). They have trouble hailing cabs, get razzed by teenage toughs, chat with the mailman, and even lose money on the stock market--and young Peter Parker has to juggle typical teen problems with fighting super villains"

This is from one of the first newspaper articles about Marvel, from the Herald Tribune back in 1966:

"Comic book super beings had mighty powers but no personality—not until Stan Lee tried out the Fantastic Four in October, 1961. The whole new tone of Lee's vision to bring human reality into comic books was set in an early F.F. appearance. (All Marvel characters quickly pick up affectionate nicknames.) This super crime-fighting team was evicted from their Manhattan skyscraper HQ because they couldn't get up the rent. The stock market investments that paid their laboratory bills had temporarily failed. The Fantastic Four, who appear in their own comic book and guest star in other Marvel publications, are beset as much by interpersonal conflicts as by super villains."

This is from the Zone:

"..as if they were happening in the same world inhabited by the readers. This is underlined by Lee and Kirby's introduction of the real world into their fantasies. In #9 the F4 go to Hollywood and the issue features guest spots from, among other, Dean Martin, Bing Crosby and Bob Hope. The dialog is peppered with contemporary references and Kirby and Lee themselves turn up..."

The world's greatest classics feature superheroes. The Bible has angels who fly and have supernatural powers, and of course Samson! Shakespeare has his ghosts, magic potions and even the occasional goddess (such as Hecate in Macbeth). Greek epics and myths had the original superheroes: Hercules, Hector, Achilles, and the gods. Superheroes were always part of the classics.

Some of the greatest writers in history employ magical realism: realistic, down to earth stories that just happen to include utterly incredible elements as if they're perfectly normal. James Joyce, for example. And writers don't come much greater than Joyce. For more details, Google "magical realism."

Superheroes, at certain times of history, are the most appropriate reflection of the real world. The world's ancient epics, for example, appeared at the start of the bronze age. Read the Iliad, placed around 1200BC. notice all the detailed description of armor. This is what made kings and the greatest warriors into superheroes: the elites had a new precious metal for their armor and swords: this new super-material allowed a single hero to defeat a dozen ordinary soldiers. Homer exaggerated their power and gave them miraculous divine help, but their story was a heightened version of what was happening in the real world: technology was creating superheroes.

It is the same in the 20th century: just as bronze revolutionized the world, so did modern technology. Modern elite heroes could fly at faster than the speed of sound (in jets), fly into space (on rockets), destroy whole cities (nuclear weapons), shoot all kinds of energy bolts from their hands (guns have kinetic energy,and new weapons promised lasers). As with Homer, the comic book writers reacted to the new world, exaggerated it, and gave it a miraculous cause, as it was indeed a miracle.

The realistic origins of Fantastic Four issue 1It is true that current Marvel heroes cannot exist in the real world. As Peter Gillis explains:

"It's a fundamental disconnect to think that a world with teleportation, undersea races, mutant nations, and gangs of superheroes would still have Paris Hilton as a celebrity focus. In fact, people living on a consistent Marvel Earth would have a culture almost unrecognizable to us: Instead of being the Crown of Creation, they'd be living with the knowledge that we're a not-very-evolved backwater planet with a sorry excuse for technology--and that immortal Gods exist and periodically tear things up. The supernatural would be a certainty, as would the afterlife--and America would have no sense of security at all, with giant robots marching through the countryside. If I were to actually craft a background that jibed with the Marvel Universe foreground, America would far more resemble Mughal India than our world of high cholesterol and YouTube."

In contrast, early Marvel heroes could exist in the real world, and this is how they did it:

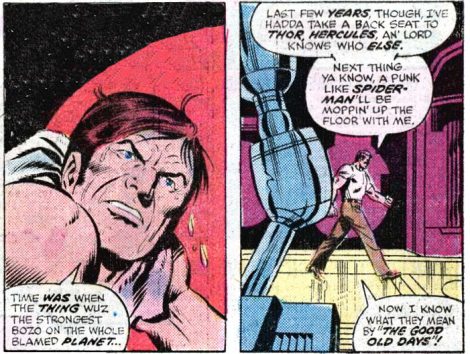

Most of the early Marvel heroes could be defeated by ordinary people. The Thing could not lift more than five tons (at first). The Human Torch could be defeated by a bucket of water, Spider-Man had to run from the police, and the Hulk was always running from the military. Any more powerful characters (Thor, the Watcher, the SuperSkrull etc.) spent most of their time on other worlds or otherwise unable (or unwilling) to interfere. There is no need for power inflation. If you know a man who can lift five tons, that's exciting! But if you know a man who can lift five thousand tons, it's impossible to relate and the story becomes dull.

"You

know what I miss? The days when Wolverine could be killed. It

seems

like, over the last decade ago, we’ve pumped the nasty little

guy up to

such a degree that he can regenerate his entire body after it’s

been

disintegrated by a nuclear blast. We’ve seen him torn in half,

cut his

head off, and still he just keeps on ticking. And that’s just in

books

I read this past weekend. At a certain point, I have to wonder:

where’s

the drama anymore?" -

Tom Brevoort, blog, 2009-04-27

In the early days there were fewer than twenty superheroes. It was possible to believe that maybe they existed out there in the real world. But modern Marvel boasts of more than five thousand licensed characters. The real world connection has been lost.

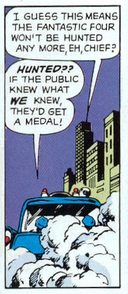

Nearly all the big events in early Marvel happen in secret. So you can believe that maybe they really did happen and the 1960s news cameras either missed it or hushed up (as they did with JFK's affairs).

Objection...

One reader wrote and objected: "But what about the early Hulk?" he said. In issue 2, page 14, and issue 6, page 12, we see events that were known to the whole world (the toad men invasion and the Metal Master's global activities). But even this proves the point: the letters pages show that the readers wanted believability. This was the only early Marvel comic to be canceled due to poor sales. When the Hulk later came back he had smaller scale adventures, and sales soared!

But after the Marvel Explosion in 1968 new writers took over, invasions got bigger, powers got bigger, and realism became impossible

The superscience and Fantastic Four technology pages of this web site are in the spirit of the No Prize: You think that the comics don't make sense? Sure they do! Hey, Stan, I want my No Prize!

Another genius move was to have the writers exist in the same world as the comic characters:

So don't worry if a story doesn't make sense: it's still real. The writers just exaggerated! Like in this example where the writers changed a Thing story so they could sell more comics. This probably explains all the impossibly powerful villains that appear out of nowhere:

The bottom line is that all the comics describe events that really happened. Realism is everything. Realism does not subtract from the fun, it adds to it. Realism is what made Marvel great.

Modern comics are grittier and have movie-like dialog. That does not make them more realistic.

Realism is often confused with "grim and gritty," meaning, more extreme violence and heroes who break the rules to get things done. Grim and gritty can never be realistic, except in "what if" stories where they all die or retire, e.g. Watchmen. This is why:

1. With extreme violence, soon every hero would be either dead or crippled.

2. Anti-heroes (e.g. the modern Batman) are only sympathetic if they never make mistakes. Heroes who never make mistakes are unrealistic.

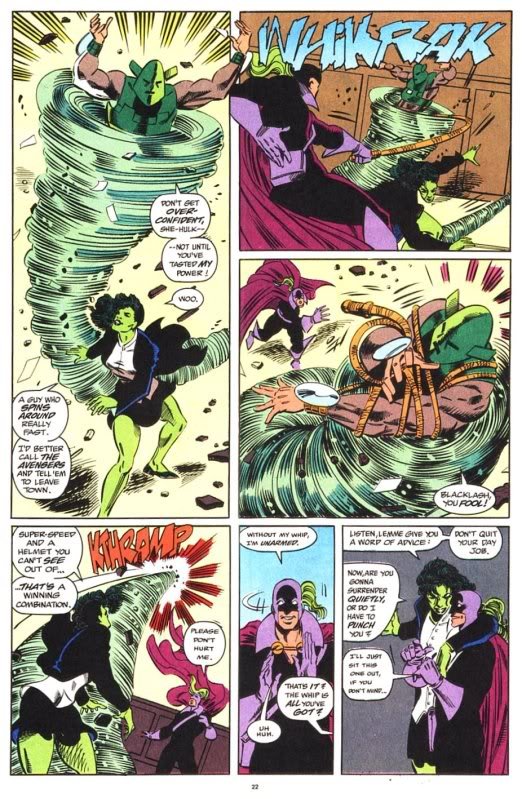

Ironically, the old stylized battles are more realistic than modern blood-and-guts battles. This is why:

Superpowers are dangerous. One wrong move and you're all dead. Where superpowers exist, wars become largely a matter of posturing, to intimidate but not to kill. We see this in the Cold War: nobody dared use nuclear weapons in anger, so the goal was to intimidate without escalating to mass death. So stylized super powered fights are more realistic than simple attempts to kill the enemy.

We can learn from Shaka Zulu.

Super beings are like the old Zulu tribes. Battles involve a lot of posturing and spear shaking, and warfare can continue for generations. But then Shaka Zulu came along, and he focused on more efficient killing. So he quickly defeats everyone and stability ended. For a stable costumed population you need to have wars based on proving your ability, not based on blood. As soon as a grim and gritty leader appears (like Shaka Zulu) then the game is over.

So for superheroes to exist, the only realistic kind of battle is the flamboyant ritual fighting of the silver age, not the bloodletting of modern times.

Many comics have cinema envy. They try to imitate Hollywood 's version of "realistic" dialog: very few words, and carefully chosen. But cinematic dialog is less realistic than compressed didactic dialog: superheroes are like the emergency services. In the real world, the emergency services have to communicate clearly: they use flat, explanatory dialog because ambiguity can mean death.

When off duty people talk in a verbose fashion, and often state the obvious just to make conversation. Contrast this with the sparse dialog in modern comics, where it's hard for new readers to know what's going on.

There are two areas where old style dialog was unrealistic on the surface, but these contributed to greater realism overall:

Cliche language:a character (especially a villain) would often speak in cliches. This enabled a reader to quickly understand the sense of what is going on. Communication is more important than verisimilitude.

Modern comics are also seduced by Hollywood glamor: characters inhabit a world that their readers do not. An early example of this is when DC de-powered Wonder Woman to make her more like Emma Peel. But her world of high fashion and money was no more realistic than her world of ancient gods.

A Kirby street scene, full of ordinary people but only one amazing thing, is more realistic than a modern comic where everyone is wealthy and handsome.

Modern Marvel editors have sacrificed realism in favor of merchandising. It is justified as preserving what the characters "should" be. But by keeping the characters the same you destroy the real underpinning: realism. Doc Nebula explains why so I won't repeat the arguments. Eric Larsen puts it succinctly:

"I guess that’s part of the reason I stopped caring. It wasn’t just that every character seemed to get a new voice and personality and face and physique when handed from one creative team to the next, but often everything that came before was ignored, contradicted or written off as somehow not real. It’s at a point where I can no longer believe that these characters are the same people anymore and it’s to a point where I can’t get caught up in their adventures because I know that somewhere down the line, whatever had happened will be tossed out the window just as everything else had been countless times before. "Some people mumble apologetically "but it's just a comic." Shame on you! Demand more! The early comic writers and readers treated their comics seriously, and the result was better comics!

J.R.R.Tolkien probably knew more about fantasy than anyone. In his essay "On Fairy Tales" he gave the right way to approach it:

Fantasy must make perfect sense within its own world.

Why? Because the purpose of fantasy is to let us see our own world from a new perspective.

This is why we need continuity. By making one part unbelievable we make it whole thing unbelievable and thus pointless. And this is why it is dangerous to be too stylish: it is not our world. We cannot relate.

Readers with low expectations often appeal to the suspension of disbelief. This shows a fundamental misunderstanding of the concept:

Coleridge had faith in his stories

Coleridge invented the term "suspension of disbelief:

"that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment, which constitutes poetic faith"

Notice that last part? Suspension of disbelief is a form of faith. Faith means you trust that something is real, even though you don't analyze it. To suspend something (in this context) means to make it wait. The answers will be forthcoming, but not yet. Coleridge was talking about his poem the Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner, because it refers to spirits. Coleridge believed that spirits were real, and he was asking his audience to just accept it for now, because they could discuss the details later.

Horace wanted explanations

The Roman poet Horace is credited with an early example of suspending disbelief in his ars poetica:

...et idem indignor quandoque bonus dormitat Homerus

(... and yet I also become annoyed whenever the great Homer nods off.)

He is saying he does not like it when a writer falls asleep on the job and includes inconsistencies. Horace, like any good reader, wants his stories to make sense! (Luckily Homer's mistakes can easily be explained away by saying later copyists made mistakes, just as The Thing complains that Stan and Jack make him look uglier than he really is.)

Shakespeare reported on real facts

Shakespeare asks the audience to overlook problems in Henry V:

"[...] make imaginary puissance [...] 'tis your thoughts that now must deck our kings [...] turning th'accomplishment of many years into an hourglass."

Notice his explanation: he's reporting the acts of real kings, and merely compressing the events in time. It's the same explanation as used in the Thing story: these are real events, and any problems are due to editors who have to fit the constraints of the medium.

The modern version of "suspension of disbelief" is nonsense

In modern times, "suspension of disbelief" has been twisted to mean "we don't care about this part." But this just causes more problems. If you don't care about one part (e.g. Superman's disguise) why do you care about other parts (e.g. he can fly)? If you chose to accept one part as nonsense then you pretty soon have to accept everything as nonsense.

Tolkien on Marvels

Tolkien explained the whole purpose of marvels (he was not referring to comics, but this applies to all fantasy). Marvels exist for us to marvel at: to make our minds expand and race, not to shut them down.

"since the fairy-story deals with 'marvels,' it cannot tolerate any frame or machinery suggesting that the whole framework in which they occur is a figment or illusion."(Note that this refers to drama: a lot of comedy relies specifically on breaking rules.)

Remember that quote from Kirby?

"My stories were true. They involved living people, and they involved myself. ... If you analyze them, you'll find that I'm not really fictionalizing. There's a realistic ending, there are realistic circumstances, there are realistic beginnings and consequences"

Contrast that to the views of Tom DeFalco, who was editor in chief when the Marvel Universe died:

"DeFalco: People have often said to

me “I don’t read SPIDER-GIRL

because it’s not real!”

"(laughter)

"Interviewer: Like SPIDER-MAN really is real?!

"DeFalco: And I’m like “Uh, guys…”

"(laughter)

"Interviewer: What did Alan Moore say? “This is an imaginary

story… but

aren’t they all?”

"DeFalco: Aren’t they all! And Alan, as he often does, just

nailed it.

"Interviewer: Nailed it."

(source)

Or as Dave Mazuchelli puts it,

"Superheroes by their very nature are absurd, and the more you try to explain them, the more absurd they look." (Dave Mazuchelli on the back of the Batman: Year One hardcover)

Notice the difference? Today, realism is openly mocked:

Q:

Is there any chance of a more mature Spider-Man book coming out?

Spider-man's schtick is that he is a very relatable character.

It would

be nice to see him in the most realistic as possible.

A: In the most realistic manner possible, Spider-Man would be

dead of

leukemia.

- Tom Brevoort. >

Buy the same logic, Spider-Man would not be Spider-man, so Brevoort's logic is flawed. Spider-Man's form of radiation was clearly not conventional.

Here's a similar quote:

Q:

Which comic universe do you think is more possible to be real in

this

world? Like which universe can work in our world? Marvel or DC?

A: I don't think any comic book universe is particularly close

to

reality--that's why all of this stuff is fantasy. of the two,

marvel is

on the whole closer to the real world, I think, but that doesn't

mean that our books are completely realistic. As it

turns out, men

can't fly in the real world.

- Tom Brevoort

again.

Men can't fly? Don't tell that to Yves Rossy, the Swiss jet man. Comics merely suggest the discovery of more compressed alien energy sources. It's not a huge leap of the imagination.

Q:

"Why not have some villains subjected to hardball consequences?"

A: "Because we're not working in the real world, and next month

we're

going to need villains for our heroes to fight as well, so it's

not a

good idea to kill off a bunch of those characters. This is

fiction, it

doesn't always have to reflect reality that

closely."

- guess

who

You can't kill off villains? Marvel claims five thousand characters. Clearly it isn't that hard to make new ones if you lose a few. Is realism so unimportant?

The modern lack of realism is so well known that you can make a modern comic look like an early Marvel just by placing heroes into a realistic setting:

Pete Woodhouse: "The splash page is very reminiscent of Marvel

(members of

the public reacting astonished to hero-in-their-midst is very

early

Marvel)[. ...is this] a conscious effort by DC?"

Brian Cronin: "I would say it was definitely conscious."

The success of the Fantastic Four spawned a whole universe of

comics. But the other comics are not as real. This is how we know:

There is another explanation for all the impossible stories: Mystic Marvel.

Every Marvel title has a half hidden undercurrent of magic. In some it is explicit (Dr Strange, Excalibur, etc.). In others it is more subtle (the community of Salem in the Fantastic Four, or the Juggernaut and Cyttorak in the X-Men). Nathan Adler, in his Fanfix blog, argues that mystic forces are central to the X-Men, and mutants are not what they appear to be. The Dr Strange comic describes titanic secret battles with higher beings who wish to remain largely hidden. So these are the real story of Marvel and the superheroes are merely the surface. The mystic forces could have their own reasons for keeping the world as it is, and that is enough to explain anything odd in Marvel Comics.

This is a huge conspiracy theory, but there is evidence for it everywhere. It would take years to develop this coherent theory of magical realism in the wider Marvel Universe, so I won't even begin to try. For convenience I apply Occam's razor and just say other comics as less canonical than the Fantastic Four, but I acknowledge that this is not the only possible view.