|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

More details:

The spikes are because I chose just a single issue in the summer and one in the winter. I think it helps to remind us that sales always fluctuate, with sales in summer generally higher than winter. These fluctuations explain why publishers don't always spot trends. A helpful visitor to this site averaged the original data for use: I've included his email at the end of this page. The table covering 2002-2006 is based on data released by Heroes World and Diamond, the two distributors that control almost all comic sales. The figures are not strictly comparable with the other chart because they are measured in a different way (usually the top 300 north American sellers from Diamond) but the industry treats them as the most accurate guide. Once again I chose January and June figures (where available) as representative of summer and winter sales.

Recent data are not gathered in the same way, so here are some actual numbers in separate tables:

1966 average sales of Superhero comics (the year before

Marvel broke into the top ten)

|

1969average sales of Superhero comics (after the price increase to 15 cents and the Batman TV series ends) source

|

2009September sales of Superhero comics (now priced 2.99-4.99) source

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Details

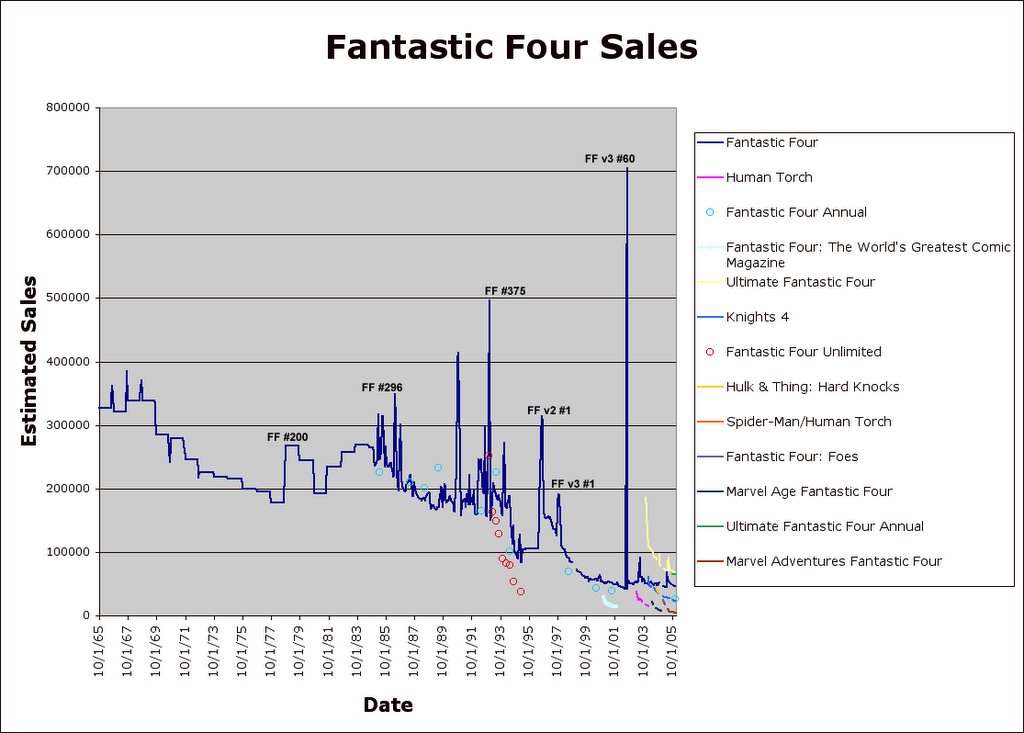

Fantastic Four graph created by Sean Kleefeld and used by kind permission. Thanks, Mr K! All comics have different, but the FF sales reflect the industry as a whole. Details of how he compiled the data are on his original blog entry. The spikes are special issues that are heavily promoted to fans, especially during the crazy investment bubble of the early 1990s that almost destroyed the industry, and the heavily promoted relaunch in 1996. The only long term sales improvements were at the start (obviously) and under Jim Shooter in the 1980s. Other than that it's been a steady long term decline, with a small improvement after 2000 due to abandoning the worst practices of the 1990s, selling trade paperbacks, and publicity from a string of successful movies.

"Richard" from the comicbook.com forums posted these numbers in July 2012. He then posted sales figures for the Fantastic Four. This illustrates the difficulty in measuring numbers in the modern age: titles end, start, renumber, double ship, etc. The only long term trend is slowly downwards, with a shift in emphasis to movies and merchandise.

"I just saw the figures for

January 2012 and the entire top ten is taken up with DC titles.

(What's so thrilling about Aquaman?) The top selling book still

sells less than 140,000 for that month, and The Amazing

Spider-Man isn't even in the top 20. Wow."

| Fantastic Four |

chart position |

sales | Future Foundation |

chart position |

sales |

| 588 | 5 | 63,529 | |||

| After issue 588 Fantastic Four was replaced with "Future Foundation", then the main book came back with issue 600. A similar relaunch and renumbering occurred after issue 416. | 1 | 1 | 114,472 | ||

| 2 | 5 | 69,790 | |||

| 3 | 5 | 66,885 | |||

| 4 | 7 | 60,571 | |||

| 5 | 5 | 58,925 | |||

| 6 | 18 | 55,601 | |||

| 7 | 21 | 54,022 | |||

| 8 | 19 | 51,917 | |||

| 9 | 34 | 53,091 | |||

| 10 | 40 | 49,642 | |||

| 11 | 41 | 48,433 | |||

| 600 | 15 | 73,809 | 12 | 39 | 49,449 |

| 601 | 29 | 51,080 | 13 | 36 | 44,970 |

| 602 | 36 | 45,131 | 14 | 39 | 42,609 |

| 603 | 37 | 42,419 | 15 | 40 | 40,583 |

| 604 | 34 | 42,126 | 16 | 43 | 37,152 |

World War II: the golden age

Our story begins in the early 1940s where some individual comics sold by the million. If memory serves, Superman's top sales were 1.6 million copies an issue, but the original Captain Marvel hit the record at 2 million. Note that these were not specially hyped issues. In the 1990s Marvel managed to sell 1 million copies of one issue of one comic, but only by extreme hype (and collectors buying multiple copies). Sales in WWII were genuinely high without the need for hype. After the war the stories became more bland and sales decreased. So fast forward to...

1955-1957: restricted distribution

At the start of 1957, Marvel (then called Atlas) was the biggest comics publisher in America and published 75 comics a month, with 5 stories per comic. But as a result of the campaign against comic violence by Fredric Wertham, comics got very bad press. Many retailers and distributors stopped taking comics. Many comics stopped publication. Atlas (Marvel) lost its distributor and one month produced no comics at all. To survive, Marvel had to take a very restrictive contract with National Periodicals, DC's parent company. Marvel was only allowed to sell eight titles a month. Writers and artists were fired. For a few months they just used up the work that should have gone into the 75 previous titles.

1958-1960: they try something new

In 1958 Jack Kirby came knocking on Marvel's door. Depending on which version you believe, either this was coincidence, or it was Kirby who persuaded Stan Lee to go to publisher Martin Goodman with ideas for new comics. They experimented with various ideas but nothing took fire. In 1960, DC published the Justice League and it sold well. Goodman suggested that Marvel do a superhero team, and Lee's wife suggested that he put the same effort into it that he put into his other projects (TV scripts etc.). The Fantastic Four began in 1961 and the rest is history!

1961-1968: Marvel's sales soar

Marvels' books sold more and more each month. Eventually the Marvel style was copied by DC and their sales improved as well, but not as much as Marvel's. Marvel still had to distribute through National until 1968 when Marvel was sold to another company (that later becomes Cadence Industries). In 1969 this company bought its own distributor, so Marvel could publish as many titles as they wished. Around this time the extra titles (and continuing strength of the other titles) allowed Marvel to overtake DC in sales numbers, and they have remained higher ever since.

This house ad for retailers sums up the era:

The increase in sales led to two decisions that, in my opinion, killed the goose that laid the golden egg. First, Marvel was able to publish more titles. More titles means less tight continuity between each title, it meant fewer readers would buy the whole range (and so feel less invested in the titles), it means less pressure to make each issue an event, and it meant creative talent was spread thinner. (Some, like Jack Kirby, left Marvel at this time). Second, they invented Marvel Time as a way to keep the same heroes around for longer. Change ended. The fans noticed.

1968-1971: sales flatten and start to decline

"Comics had always been a cyclical business, and almost everybody in 1971 thought that super heroes must inevitably be on their way out again. That's why there was such a gold rush on to find the next big genre--sword-and-sorcery looked like it might be a contender, and there were a lot of new mystery (watered-down horror comics without much horror), war and western comics being churned out in this period. But the classic Marvel, Stan's Marvel, was still seen as something of a fad (even by Stan himself), and the common wisdom was that everybody was going to be doing something else very soon (possibly in another field entirely.)" - Tom Brevoort

Also, in October 1971 Marvel used a sneaky trick: they raised their page count and price. DC heard in advance and did the same. But DC had to buy their paper a year in advance so were locked into the higher page count. The next month Marvel dropped their pages and prices again, while DC had to keep theirs high. For the whole year Marvel grabbed market share, kept a lot of it even after DC went back to normal.

The early 1970s: sales go down

"Newsstand sales were dropping precipitously in the early 1970's in the face of alternative forms of entertainment (especially television), and fewer and fewer retail outlets were even bothering to install a spin rack. [the industry seemed to be] on the edge of disappearing forever" [1] The comics companies were in trouble. "That was the period when comics seemed to increase in price every year, with the price quickly escalating from 12 cents, to 25 cents, in just four years." [2] Even at 25 cents, distributors only got 5 cents per issue, and most issues had to be returned, so when sales went down the retailers were happy to stop selling them and make space for more profitable magazines. "Independent News distributed DC in 1970. They made 80% of their money from 3 magazines: Playboy, Penthouse, and Mad. The comics were not significant to them." (Fake Stan Lee)

Note that the absolute figures did not decline so much, but when margins are tight and newsstands make more money using the space for other magazines, then a ten or twenty percent decline is deadly. Also during this period "Marvel captured a significant piece of DC's market share by offering a lower-priced product with a higher distributor discount." (Wikipedia)

The late 1970s: sales go down even further

"The late-1970's nearly saw the demise of comics publishing. The precipitous drops in newsstand sales that I mentioned earlier in this series more than offset the ability of Seagate Distributing to grow comics sales by shipping comics directly to comics shops. While the Direct Market comics shops did manage to transfer a great number of fans to themselves that otherwise had been purchasing through newsstand outlets, the harsh reality was that newsstand sales were dropping far faster than the Direct Market was growing. ... DC Comics, without warning, suddenly slashed over 30% of their entire line in a single day (the infamous DC Implosion [of 1978]...). [Regarding Marvel there was a] marked predisposition on the part of Mr. Feinberg to simply shut the whole thing down." [3]

1977: Star Wars saves Marvel from bankruptcy

According to Jim Shooter, Marvel would have gone bankrupt in the late 1970s if it was not for Roy Thomas fighting to persuade them to do a Star Wars comic. Those sales were the one factor that kept Marvel alive.

1978: The DC Implosion

As noted, in 1978 DC cut a third of their line in a single day. Back in 1968 Marvel had doubled its line with The Marvel Explosion, and in the early 1970s increased the page count. DC countered with "the DC Explosion": more comics and more pages (at a higher price). Marvel quickly dropped its prices, grabbed even more market share, but both companies continued their decline. The bad winter of 1977-78 made it worse, leading to DC's drastic decision.

1979: Shooter starts to turn it around

Due to a continuing decline in sales, pressure from parent companies, and a new lawsuit affecting distributors, Marvel was in crisis. However, in 1977 Jim Shooter had started to turn the place around so that books came out on time and with quality stories. Chuck Rozanski wrote a letter suggesting better credit terms for comic shops, Shooter understood comic shops, and so Marvel decided to deal with them directly under attractive terms. In 1979 the Direct Market accounted for 6% of Marvel's gross sales. In 1982 it was 20%. In 1985 it was 50%. In 1987 it was 70% of Marvel's gross sales. DC followed suit. As specialty shops grew there was space for new titles, and independent comic publishers sprang up. "It wasn't until the 1980s, and the real advent of the direct market as a legitimate means of distribution that most people began to think that the business as a whole might still have a future." - Tom Brevoort

1979-1993: Jim Shooter + investor speculation = rising sales

Rising sales are partly due to Jim Shooter's time at Marvel, which produced some classic stories. And partly because people started to make serious money from back issues, so the number of comic shops soared as everyone thought they could make a good living from their hobby. Also at this time both Marvel and DC had policies in place that led to a smaller and smaller number of distributors controlling all comic sales.

1993-1999: the bubble burst

A combination of too many new comic shops (a classic investment bubble) and a series of bad decisions at Marvel (such as great increases in cover price and number of titles) all started to fall apart in 2003. The last straw was DC's Death Of Superman in 1992. Fans invested in the last issues expecting high returns, only to find it was all just a trick. Collectors lost interest. Marvel tried more gimmicks and price rises to maintain their income, and bought the distributor Heroes World and stopped selling through others, hoping to force the industry to play by its rules. Marvel was bankrupt in 1996 (they filed in January 1997), but was able to continue trading under new terms. The move to specialist shops had saved the industry for a few years, but long term it threatened disaster. Only existing comic buyers go into comic shops, so there are no new readers. In 1979 a typical comic sold 100,000 copies, and much more ten years earlier. But today, 20,000 is common, and comics only survive because they make extra sales in trade paperback compilations.

"Sales of comics had dwindled steadily since 1993, the most profitable year in comicdom's history: According to the January 18 [2002] issue of Comics Buyer Guide, the industry's key trade publication, sales fell off 14 percent in 1998 and 5 percent in 1999 and 2000. A billion-dollar biz in 1993 was, by 2000, pulling down less than half that." (source)

Note that, despite greatly reduced sales, the publishing arm was still profitable. Kurt Busiek wrote: "Marvel's bankruptcy had nothing to do with publishing. The comics were profitable during the whole period. The owners of the company leveraged the company into huge debt buying other companies, and then couldn't hold up under all that debt."

Since the 1980s: merchandising is everything

To understand Marvel comics' sales since the 1980s, you need to know four things.

"Mega-investor Ron Perelman has all the traits of a comic book super villain. He's massively wealthy and powerful. More to the point, he exudes enough vanity and overreach to make Lex Luthor and Dr. Doom seem like a couple of Girl Scouts." source

This was always true to an extent: Stan Lee had to do what Martin Goodman said, but in the early 1960s he was pretty much left alone because comics were not considered important, and fans could not be persuaded to pay more than ten cents. Now that comic characters are brands with asset value and loyal fans, that has changed.

Distribution, promotion and other non-story related variables: these always had a big impact on sales. A great comic can sell badly and a poor comic can sell well in the short term, and as business cycles speed up the short term is all that matters.

2000-2006: slow improvement due to trade paperback sales

2000 saw the worst sales figures. Since then sales have slowly improved (only slowly) because Marvel has had success with selling trade paperbacks. Trades typically collecting six issues of the monthly comics. Now comics are written in six issue blocks with the trade paperback in mind. Many commentators believe that monthly comics are effectively dead, except as source material for trade paperbacks. The trades and comics together only exist in order to provide source material for the far more profitable movies and merchandising. It should also be said that the quality of writing and art has improved. In the 1990s a lot of top name writers and artists left to create independent comic companies. Part of the revival in sales is due to bringing them back. Personally I think a lot more could be done, but credit where credit is due.

Marvel makes much more money from brands than comics

"By May 2003, Marvel was back in profit, having had a colossal boost from royalties from the Spider-Man, X-Men and Daredevil films." (source)

"The company reports in 4 different segments:2008: monthly comics go up and up in price, publishers focus on the trades

"Dean" wrote: "[While monthly sales are] utterly flat, the total market is booming. This is a market that looks more like the book business than the magazine business. These are bound volumes that are sold through book stores and Amazon.com as well as the local comics shop. This portion of the market has grown from 20% of the total market to over 60%. Pretty clearly, this is the market that is driving the bus in comic business. That is the source of the revenue growth. The periodical business is a classic 'Cash Cow' for the so called Big Two publishers, who have a combined 75% market share. A smart business person would not invest resources into a Cash Cow, beyond what is necessary to maintain it."

Trade sales are not as hopeful as they seem

It's tempting to think that trade paperback are bringing comics into mass market book stores, but most are to comic shops or on line to existing comic fans.

"It's easy to assume from this that Marvel's growth in bookstores has largely hit a brick wall -- but then, you could come to the same conclusion simply by visiting a Barnes & Noble graphic-novel section, where the shelf space allotted to Marvel books has at best held steady and at worst actually lost precious space. (One bookstore manager described Marvel's sales at her location for me as "okay when there was a movie out, but otherwise negligible.")" (source)

2011: Marvel cuts costs, DC "draws the line at 2.99"

In 2011 DC resisted Marvel's trend to raise the prices of comics from $2.99 to $3.99. DC also relaunched their entire line, mostly at $2.99. Also in 2011 Marvel took a number of cost cutting measures: (source) page rates were cut, inventory was cut, staff who left were not replaced, staff are kept as temps rather than hired full time to save on medical costs, and so on. Anecdotal evidence suggests heavy reliance on unpaid interns. This is of course a time of recession in the whole western world, but sales were declining even in the boom period.

2012: Double shipping, movies and DC's "New 52"

2012 saw three trends.

2013: "New 52" temporary sales boost ends

"Data below (Top 300 Comics tab) shows that for the four months leading up to "52" an average of about 5.8M books were sold by all publishers (Yes there are others besides DC and Marvel). In September with the launch of "52" this number increased 25%. About a 1.5M more books were sold. Six months later (actually it only took 3 months), the freshness of "52" has wavered and basically we are back to status quo." (From analysis on "Cyke's optic Blasts":) The industry appears to believe that declining sales are inevitable: Q. How do you feel about the declining Spider-Man sales

post-OMD?

A. I think that they're very

much like the declining sales of X-MEN and NEW AVENGERS and

every other book in the line--pick one. - Tom Brevoort

2014: the most profitable month ever (what? did I read that right?)

The top selling comics today sell one tenth of what they used to

sell. There are 30,000 towns in America, and one sale per town puts a

comic near the top ten sellers. The worst selling comics are often below

ten thousand issues. So the publishers must be bankrupt, right? No:

they have ten times as many titles, and charge three or four times as

much per issue (after adjusting for inflation). In August the Christian Science Monitor reported "July 2014 is the most profitable month ever in comic book history, and comics are only getting bigger."

And of course the movies and merchandising bring in many, many times

that revenue. Stan Lee worked out of a single office, but now Marvel has

a big flashy global headquarters. The future looks even brighter: the

movies are raising awareness of superheroes, and the industry is slowly

learning how to sell via the Internet, which solves the distribution

problem, always the biggest problem in comics. Comic sales are so small

that it would not be difficult to double them and double them again if they get it right.

The bottom line is that the comics industry is mature, and so it knows how to make money.

So why am I such a pessimist? Because these are "just comics." All

the fans tell me that. They are "just comics" and should not be taken

too seriously. They are not on the same level as real literature. They

contradict themselves, they expect readers to lose interest in a few

years, they are short term fun, with a bit of sex and violence mixed in,

or else they pander to nostalgia. They are small stories with small

ambition. These are not the comics that inspired me and millions like me

in the 1960s to 1980s. For a brief period in the 1960s some people

dared to believe that superhero comics could be real literature, to the

highest standards. Those days have gone. The dream is dead, at least in

the superhero genre. At least in my opinion.

Once upon a time a large proportion of fans would be "Marvel Zombies", buying the complete line of comics. This is what it cost each month:

The number of Marvel Zombies is now almost zero

Sales and profitability are not the same

John Jackson Miller knows a thing or two about sales, and made some interesting observations on a recent comic price guide thread. This is just a “fair use” summary, with my comments:

The comic book with the largest print run of all time was 1991’s X-Men Vol. 2, #1, with 7.1 million copies across five variant covers. This was a good quality book, but was also the greatest example of hype at the most hyped period of an investment bubble. The investment bubble peaked and burst in 1993. More comics were sold in 1993 than in any single year of the Golden Age.

The highest selling single comic in most years is now in the 300,000s. In 2003 Superman The Wedding Album had 346,000 pre-orders, and around the same time the “Heroes Reborn” Fantastic Four first issue had pre-orders of 314,000.

By the end of 2005, comics in the USA were grossing around $30 million per month. This is for the top twenty publishers handled by Diamond (which has an effective monopoly), and includes a few publications that are arguably not comics, but overall the figure is taken to be a reliable ballpark. The number was increasing by three percent per year.

Typical sales figures in 1968 (the height of the silver age) were 200,000 copies per issue. Typical sales for a hit book today are around a third of that. But they make around the same money, even after inflation, due to higher cover prices and reissuing through trades. Licensing can make them even more lucrative.

Recent years have had more than double the number of releases seen in 1968. But perhaps the best news is that comic professionals are now paid more (usually), and of course the comics are printed on better quality paper.

Beware - do not draw conclusions from single issues

The major publishers do not release their actual figures if they can avoid it, so most published rankings are based on estimates, e.g. comparing orders to a reliable seller like Batman, and extrapolating. This is good for a general trends, but Tom Brevoort warns against relying on this for individual titles and especially not for single issues:

"As I have said time and again until my mouth is sore and my throat bleeds, all of those numbers that folks like you dig up around the Internet to bolster whatever argument they're putting forth are inevitably wrong. They are not correct, they are not accurate, they are in error, they are wrong. I understand that you're working with the best data and information that you have, but can we please take it as a given that I am working with better and more complete and more firsthand data than you are? I don't mind being corrected when I'm in error, but when you're talking about speculative on line estimates based on the ranking of titles sold and how they compare to BATMAN, it's a bit ridiculous. I expect that if you look hard enough, you can find evidence that the world is flat and that gravity is a confidence trick. I'm sure the figures are out there."

To the fans, the concept of sales is easy: good comics sell. They might not sell well at the time (depending on fashions, distribution, pricing and promotion), but if the comics are created for the long term market then the other factors will average out. Hence early Marvel comics can be sold again and again, in multiple formats, and spawn movies and merchandise, whereas new comics are instantly forgotten.

To professionals, sales are much more complicated. A business needs to make its money right now, and questions like fashion, distribution, pricing and promotion make decisions very complicated. Selling in multiple formats, difficulties in measurement, corporate strategies that may focus on certain brands, and the need for synergy with merchandise make the decisions even harder. To make things worse, the accountants who focus most on the numbers don't actually read the comics and may not understand readers, whereas the editors who know the readers and comics are distracted by the day to day chaos and politics of business. But over the long run all these things become less and less important. All profit is finally traced to people wanting to read the comics, sometimes decades after those comics were created.

So fans, if they look at the long term, have a clearer view of

the forest while professionals are busy with the trees.

I just stumbled across this interesting piece on Sean Kleefeld's blog, with details by Tim Stroup. 1963 was the high point of new characters being created. This page from the Ayer advertising directory gives all publishers beginning with M (including Marvel), and each publisher's list of titles, and total monthly sales. Click for a larger image. Strangely this list does not include the newer titles (Fantastic Four, etc.) - I don't know why.

The Ayer Directories were intended for advertisers, and grouped a publisher's titles into groups, and subdivided into units (red unit, yellow unit, etc.) Advertisers would buy a space in all titles in a unit, which is why the same ads appear in all Marvel superhero comics. Romance comics were in a different unit, and Martin Goodman's non-comic magazines were in a completely different group. Marvel comics group is called Marvel Comics group because of advertisers' need, not because of distribution needs or users.

Meanwhile, Wholesalers got whatever pile of comics the distributor gave them, they didn't usually order individual titles. Before 1957 the situation was more complicated, with more groups and units.

"If you ordered the Marvel

Comics Group of comics, you got Strange Tales, Tales of

Suspense, Tales to Astonish, Amazing Adult Fantasy... Lots of

aliens and monsters and whatnot. And eventually, in 1961,

something new called Fantastic Four featuring another big

monster on the cover." - Sean Kleefeld

Gradually superheroes filled the monster books, and new

superheroes replaced the romance books, and then in 1968 Marvel

got a new distributor and could basically do what it wanted. And

the rest is history.

Digital distribution

"Q. Is it possible for comic spinner racks of old to make a comeback in local convenience stores?

A. There is absolutely no chance of this, and there hasn't been in many years. When it comes to convenience stores, each square inch of territory needs to bring in a certain amount of revenue, or it gets changed out for something more profitable. And back in the 1980s, the owners of such stores found that they could generate more income by placing video game consoles in that space. These days, the whole of mainstream magazine publishing is in free fall, so sales from that quarter are worse than ever before. It's far more likely that the digital realm will become the new equivalent of those newsstand racks, when most people have a smart phone and can download the content directly from an App."

Short term comic sales depend, distribution, promotion, and fashions. Long term comic sales depend on the quality of the story. But the medium?

Chuck Rozanski probably knows more about selling comics than anybody in the world. He created Mile High Comics, the biggest dealer, and has been selling comics since before most of us were born. He saw the end of the silver age, the rise of the Internet, and he has adapted and thrived. Marvel and DC have more accurate sales figures, but they only see one narrow slice, and they deal with merchandise and movies pressures. Chuck only sells comics. The ideas on this page come from "Tales from the database". Direct quotes are in red, the rest is my summary, so apologies if I get any of it wrong.

1. Aggressively seek new customers

"The risk that I see the mainstream comics publishers taking right now is that they are not working aggressively to build a new audience for comics. They are sitting on their hands, while watching unit sales of mainstream comics steadily decline. Their only real answer to this problem has been to continually offset their unit sales declines by repeatedly raising cover prices. This is a strategy of doom for comics as we've known them for the past 70 years." - Chuck Rozanski

2. Don't charge too much!

The core of the comics business is the loyal fans who buy the whole line of comics (or at least a large percentage). When prices rise too fast they stop buying everything. And of course new readers are less likely to start up. The readers in the middle (the ones who maybe subscribe to two or three books) will keep reading, but when you hit the core readers and the new readers you soon have serious problems. In 1986, the comics cost 65c. By 1989 they were $1.00 By 1996 they were $2.00 Today they are $2.99 or $3.99. That is a huge price increase!

3. Previews

Publishers need to make it as easy as possible for retailers (and readers!) people to "try before you buy." (This comment was made in 2001 and the Internet has improved things since then, but anything that makes it even easier is a good thing.)

4. Make web sites fast, easy and pleasurable

Many comic web sites seem afraid of giving too much away. And even worse, some plaster their material with ads. That drives people away. The goal should be to get as many people to see as much as possible. A percentage of those who see the sample will then buy the full product, and the numbers can be very large indeed.

"Sell comics, not ads! Make the experience of reading sample comics on line as fast, easy, and pleasurable as possible. Anything that interferes with that core goal [such as ads on the site] should be eliminated. ... Our experience has been that the more information provided to fans about their favorite creators, titles, and characters the greater their propensity to purchase upcoming items. Sheesh, this isn't rocket science..."

( That was written back in 2002 or 2003 I think. So I visited Marvel.com to see if anything had improved. I wanted to be able to click on a book like at Amazon's home page. Instead I was faced with two very large animated banner ads for Superman on DID! Superman is not even a Marvel brand! Marvel treats its home page like some free amateur web space that has to be paid for with ads from other people. It's all very depressing. Comic fans often talk about how the newsstands no longer stock comics, and this stops new readers from discovering comics. But Amazon has shown that the web can be a virtual newsstand, but much more profitable. It depresses me to see that Marvel has not caught on after all these years. the DC web site is better, because comics are more prominent and the ads are smaller, but they need to be like Amazon or eBay or the other really successful sites: stop advertising others' stuff, and make a virtual store front where it is easy to browse a variety of wares. )

5. Get Google to work for you

The comic companies have some very high profile brands. These should be driving people to the company web sites and thus to buying comics. But instead when you Google a superhero's name, the publisher's site is usually not even in the top ten!

6. Don't trick the fans

The 1990s saw a number of tricks that really annoyed the fans. Small things like endless novelty covers or renumbering at number 1, and big lies like "the death of Superman" where he never really died. People get tired of too many gimmicks, and if you lie to them then they won't trust you. People are more likely to stop buying if they don't trust you.

7. Produce a reliable and interesting product

Delayed, disappointing or dull products mean readers buy fewer comics.

8. Work on getting comics accepted as helping kids to read

Schools and libraries may be the equivalent of yesterday's newsstand, as a way to introduce new readers. Of course you then need to direct them to the web or the shops to actually pay for the next copy :) Don't try to make money of this, see it as promotion (and of course a way to get kids to read). Crossgen had an excellent school-oriented reading pack that was cheaper than the alternatives and was making it way into many schools. (Unfortunately the company had completely unrelated problems that drove it bankrupt, but the schools idea was a good one.)

9. Don't over-print (for the direct market)

Reducing the availability of back issues (by not printing too many) makes them more valuable. If there are more comics than people want then the price falls to almost zero. So a little shortage helps keep prices higher and this keeps comics retailers in business. Without the retailers there is no comics industry! This also increases the value of private collections. That means you and me: ordinary comic readers find that their own comics are worth more, and this encourages them to buy more. In 2001, Marvel started to pursue this policy aggressively, only printing books that were pre-ordered, and not reprinting. This was very unpopular with retailers, but popular with back issue sellers. The retailers risk can be reduced by making better previews and less empty hype, so everyone knows how many to realistically order.

10. Make it easy to open a comic shop.

In 1979, due to increased print costs, sales were declining in regular news vendors. But there were only about 800 comics shops in the whole world. Marvel (encouraged by Rozanski) made it cheaper to open a comic shop, and the numbers increased dramatically. For about ten years comic sales were better, and by 1993 the number peaked at 10,000 comic shops.

11. ...but be careful where new comic shops are located.

When a small new shop opens near an big old shop, the small shop tries to sell everything cheaper, in order to get customers. But most new shops (of any kind, not just comics) lack experience and only a few survive. Not only does the small shop go bust, but often the big shop does as well because it has lost volume and has had to cut the prices of what is left. As a result both shops close, which helps nobody. This was a great problem in the early 1990s when, helped by other disastrous policies, over 4,000 of these shops went bust by the time Marvel went bankrupt in 1996.

12. Avoid creating a monopoly

This is just common sense business advice. When you have a monopoly then you become inefficient, some of your customers have extra costs (and might go bust) and others avoid you. That is what happened when Marvel bought Heroes World distributors and used them exclusively. And when DC then made agreements with another company, Diamond, that prevented others from distributing their products. Chuck Rozanski explains at length in his columns why this was a bad move for the industry. He concludes:

"Frankly, after having spent my entire adult life working to promote comics as a viable popular culture art form, I now see us as being in an end game. It is no longer a question to me of whether the comics market as we know it is going to implode, but rather one of when this dreadful event is going to transpire. The one ray of optimism that I have managed to retain is that perhaps the day will come when those who have the power to save the Direct Market may wake up, and finally realize that the self-serving structural constraints that they have built into the current comics distribution system are strangling the Golden Goose." [4]

13. Listen to the distributors

In hard times it is easy for distributors to stop handling comics because of something like having to pay for orders in advance. These little things can cause big problems unless the publisher listens to the whole supply chain.

Keep the whole industry healthy

All the comic sellers rely on the same retailers and in general confidence in the industry. If one part of the industry suffers it pulls everyone down.

14. Don't publish too many titles

I love the Marvel universe. I would love to buy them all. A lot of fans feel like I do, and it used to be possible for most fans to do this. Most collectors can no longer buy comics on impulse (they didn't have the time or money). Substantial numbers of hard core collectors simply stopped collecting comics. The investment bubble burst.

This last point, fewer titles, also has implications for quality. As the 1968 and 1990s explosions in titles illustrate, when the number of titles goes up the quality goes down. This leads to a short term sales increase and a long term sales decline. As Steven Grant observed (in Permanent Damage, June 24th 2009):

"9 years ago ULTIMATE SPIDER-MAN was the very definition of market heat, and the line held it for some time, so what went wrong? Basically, what always goes wrong. [They added more titles.] In the mid-40s, Gleason Comics were burning up the newsstands and routinely outselling DC, Timely (Marvel), Fawcett etc. on the strength of four comics [. The publisher] looked at the accounts receivable and figured that if four books made that much money, eight books would bring in twice as much. [But] Putting the same amount of care into eight books as four was impossible, resulting in all the titles suffering creatively. [A decade later, when the industry as a whole contracted, the company was no longer special, and it went out of business.] What's the solution? The best strategy seems to be the hardest for most publishers and talent to swallow, the Biro [Gleason Comics] route: figure out what number of projects you can put your full attention and enthusiasm into, and don't exceed that number. ...Capitalizing on audience interest is a hair's-breadth from abusing their good will, and (in any medium) once you've done that, regardless of intentions, the show's over."

We forget how much harder it was in the past. Read Eisner's "The Dreamer" for how tough it was in the golden age. Then in the 50s sales collapsed (they would have blamed computers if they were around then). Marvel had just one office in 1958 when Kirby turned up, and he describes the furniture as practically on the street.

Then in the 70s the big two saw newsstands disappear. Nowadays we have comic shops and downloads, but back then it was almost impossible to get a comic out there, profit margins were razor thin and half the comics were returned. The big two considered getting out of Superheroes altogether, DC imploded, Marvel was only saved by Star Wars...

Then in the 90s the industry collapsed and Marvel went bankrupt. Life is just so much easier now for the big two. Big offices, decent page rates, fans who will pay 4 dollars for 5 minutes' entertainment... sweet. Of course sales are pathetic because the core product stinks, but financially they're stable.

People say comics can't compete with other media. Have you been on Reddit recently? It's full of comics! Strips like Penny arcade and XKCD, endless single panel memes... comics are bigger than ever. It's easier than ever to make them, and distribution is effectively free. Awareness of comic brands has never been higher: have you see those summer movie blockbusters? Batman, Iron Man, Tin-tin, all based on comics. So why are sales so bad? Let's ask the fans.

ComicbookResources recently (August 2011) had a thread for old fans who left comics, often for more than ten years, and came back. Obviously they couldn't ask fans who left comics and stayed away, as they would not be on a comic forum.) These are the reasons why fans left:

Each of these gimmicks brings short term profit at the expense of long term profits. It is as simple as that.

Back when selling comics was harder, these gimmicks did not work. Raise the prices? The kids just stop buying. Kill off a character? Most kids don't know who he is. Put the comic in a bag? It had better be cheap then, like those "three comics for a dollar" bags. When selling comics was harder, bad habits like this could not survive. But today it is always the easiest way to make short term profit. I stress "short term."

Occasionally Marvel or DC tries cheap comics, or makes a push to get comics into regular stores, or produces comics with compete story each issue. But these are half hearted attempts that never sell. How could they be anything but half hearted when the industry has convinced itself as it did in the late 1950s, that decline is inevitable?

The problems are so deep that nothing short of a revolution will fix it. That's what happened in 1938. It happened again in 1961. The first time it took outsiders, two kids called Siegel and Shuster. The second time it took a company that was reduced to a single office and just 8 titles and had nothing more to lose. It will take the same again.

For more about pricing and the half hearted attempts to produce good value comics, click here.

For more about comics that are just not good, click here.

Hi Chris,

I enjoyed reading your "The Economics of Comics" page, and thank you again for citing me for the figures you used. I have a couple of insights that I wanted to share with you that may be useful for this article.

First, I should point you toward Russ Muheras' work on the Golden Age period covering up to 1950. His data shows monthly figures across many comic book companies, not just National (DC) and Timely (Marvel). He posted his data on the newsgroups many years ago, and I kept a copy of it (it was my inspiration to do 1950 onward). If you would like, I can provide that data to you as well.

With regard to the 1950-1987 figures, I would recommend you to chart the data averaging the first half and the second half of the years. The reason is that the second half of the year typically outsells the first half, making your graph spike every other data point. By charting both halves separately, one is left with an incorrect perception of volatility of comic sales, when in fact there is usually a trend. For that reason, re displaying that graph with annual monthly figures would be more informative.

Unfortunately, that slightly complicates the years with missing data: 2nd Half 1969 Marvel, 1st Half 1976 DC & 1st Half 1979 DC. Certainly we can make good estimates based upon the other evidence. Looking at the trends for the years before and after and comparing with its rival for similarity, we see that there are some extremely good trends to rely on for this.

For example, for DC, we know that 2nd Half data should comprise around 53% of the 1976's total (it was 52.95% in 1975, 53.05% in 1977, and 53.46% for Marvel in 1976). Likewise, DC's 2nd Half data should represent about 50% of 1979's total (it was 49.48% in 1978, 50.30% in 1980, and 49.66% in 1979 for Marvel). These are extremely fortuitous similarities, making us pretty sure of our estimate. For 1969 Marvel, the relationship to DC was too stark for comparison at the time, so looking at Marvel trends is the best way to estimate 1969. For 1965, 1966, 1967, 1968, 1970 and 1971, the 2nd Half data represented 54.91%, 54.97%, 54.63%, 56.34%, 54.28% and 54.39% respectively. Thus, we would expect 1969 to have between 54% and 55% of its sales in the 2nd Half.

With that, the sales number look like this, DC in the first column, Marvel in the 2nd (asterisks around the three approximated figures):

1950 7,791,402 5,783,231

1951 8,189,473 5,622,083

1952 7,753,983 7,221,873

1953 7,500,395 5,714,252

1954 7,228,246 5,614,870

1955 6,558,787 5,233,731

1956 6,979,763 5,433,062

1957 7,865,649 3,933,820

1958 7,149,795 2,442,963

1959 7,313,258 2,486,417

1960 7,375,652 2,690,237

1961 7,328,295 3,117,459

1962 6,650,058 3,290,002

1963 6,772,973 3,755,184

1964 7,066,454 4,612,986

1965 6,642,447 5,404,393

1966 7,337,539 6,640,382

1967 6,324,335 7,042,993

1968 6,292,497 8,117,844

1969 5,285,131 8,042,000*

1970 5,491,148 7,528,171

1971 5,074,665 7,466,990

1972 4,771,124 5,830,898

1973 4,726,325 5,825,938

1974 4,316,382 6,002,617

1975 4,318,844 5,833,420

1976 3,919,000 *6,394,995

1977 4,267,838 7,009,428

1978 3,548,649 6,428,124

1979 3,113,000 *5,780,008

1980 2,801,946 5,402,625

1981 2,987,088 5,057,324

1982 3,222,133 5,985,626

1983 3,428,704 5,658,933

1984 3,102,027 6,609,716

1985 3,117,865 7,019,202

1986 2,450,440 7,156,977

1987 2,994,904 7,498,526

I hope you find this helpful. Best of luck in your pursuits."