home

Original art used to be given away

Patrick Ford

1 July 2016

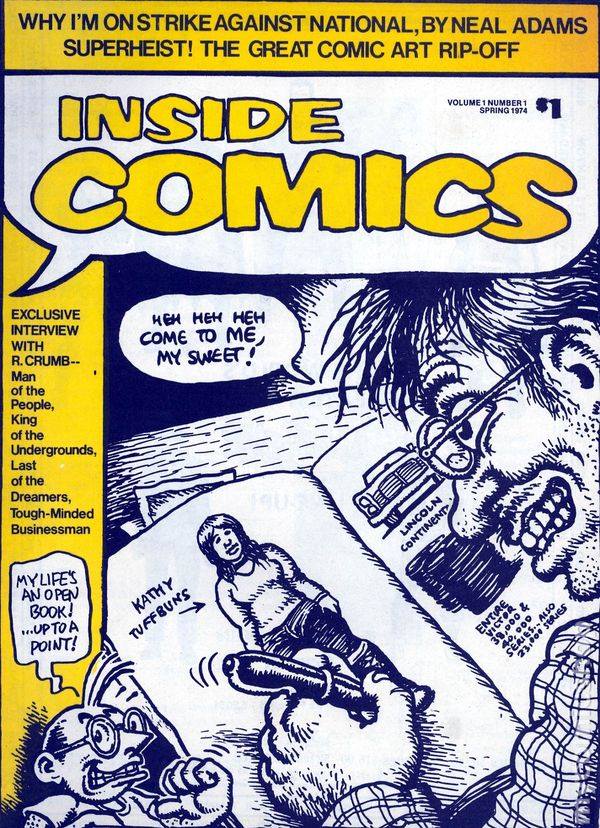

SUPERHEIST

The Great Comic Book Rip-Off

By Joe Brancatelli

First printed in Inside Comics #1 - 1974

My first visit to a comic book house came when I was about 10 years

old. When National produced comics from their 575 Lexington Avenue

offices, they'd hold organized tours of their operations every

Wednesday afternoon. As a dutiful comic book fan, I gathered several

friends and traveled all the way to manhattan. There we were, four

gawky kids from Brooklyn - smack in the middle of the country's

largest comic book house.

A balding man (who I now believe was a harassed-looking Julie

Schwartz) took us all on a grand tour. We passed writers and colorists

and artists and letterers. Kids asked silly questions - about go-go

checks or Johnny DC or something. I remember one kid asking why

someone had penciled a bra on the nude girl in the Playboy calendar.

During the tour, National gave things away. Color slides of comic book

covers, Batman and Penguin posters, comic books, and dozens of other

trinkets. And they even gave away original art work. Everybody got a

free page.

Everyone except my friend, Kevin Cadger. He got ten pages because he

didn't get any Batman posters.

That's why it came as no surprise when word leaked out that over 1900

pages of original art had disappeared from national's files. After all

the years of giving it away, or throwing it out, or shredding it up,

someone's finally lifted 1900 pages and no one was the wiser. At least

for a while.

Original comic art pages have always been treated trashily. Companies

never bothered to return them. newspaper syndicates did horrendous

things to originals before returning them. But mostly no one cared,

especially since comic art wasn't particularly valuable.

Then Jerry Bails started the whole fandom thing. the conventions, the

fanzines, the newsletters, trading, selling, buying, and the whole

spiel. All of a sudden, comic originals were worth something. And

that's when the hassles started. Artists wanted their originals back.

Knowing they could supplement their income by selling them, many

artists resorted to stealing their originals back. In fact, most of

the originals on the market in the earl;y 1960's were stolen.

"One thing I can always remember," one now retired artist said,"was

how we always had to sneak into Marvel or DC or Charlton or Warren and

steal our own stuff back. After a while, it became a game. Everyone

knew we were doing it, but they just said, 'Well, that's the way it

is' and laughed a little."

A Pocket Full of Art

But things changed. In 1970, National stopped general distribution of

original artwork, shocking artists and inflating the collectors

market.

"We had long discussions with our legal department on the matter."

said Sol Harrison, National's vice president and production manager.

"They seemed to feel that we should hold on to all our artwork. They

were really frightened that if someone had the originals to a complete

story, they would run to South America and print it. We had copyrights

to protect, and the legal department felt holding the artwork was the

best procedure."

National's policy went generally unchallenged and stock accumulated.

"We have had thousands of pages around after a years or two," said

harrison. "Eventually, we had to get a storage space, but there was

still plenty of art around the offices."

And therein lay the danger. Thousands of pages were just sitting

around at National's 909 Third Avenue set-up, waiting for some sharp

entrepreneur to make his collection. And being part of the vast Warner

Communications conglomerate, which also owned Warner Brothers, Seven

Arts, Paperback Library, Warner Books, Atlantic, Electra Asylum, and

Atco records, among others, National offices were being moved to the

warner Communications Building at 75 Rockefeller Center. After several

years of planning, the crosstown move was finally begun in the summer

of 1973.

"It was just one giant, f***ing madhouse," one national editor said at

the time. There were drawing boards, and desks, and stuff all over the

place. And artwork was scattered everywhere."

No one at National was Particularly concerned with the art. it was

stacked on skids and tied down with bailing wire. No one thought of

taking inventory and thousands of pages, worth several thousand

dollars on the fan market was unaccounted for. It was being moved from

office to office, waiting to be picked up and moved to the new

building.

"In retrospect, of course, it was a dumb move." a national production

staffer said. "Had Sol known any better, maybe there would have been

an in and out inventory. But nobody gave a sh*t. The art went in and

out and no one looked twice."

Except for several sharp eyed young staff members. most of them, lower

echelon employees, came up through the fan ranks and knew the value of

the unattended artwork. They also,apparently, knew which skids

contained the best material.

A collector who later purchased some of the stolen art for his private

collection said that "no one but and insider could have done the job.

it was planned perfectly. They got a couple of hundred beautiful

pages. It was a perfect set-up."

Another collector who bought some of the purloined material agreed.

"The plan was simple," he said. Have a friend on the moving crew

'misplace' a flat of artwork. Later, if it was discovered missing, it

could easily be found without getting in trouble. If no one noticed it

was missing, it was just taken away later."

"Certain staff members had decided to rip-off some of the pages," the

collector said. "And it was an inside job."

Naturally, no one ever missed the 'misplaced' skid and it simply disappeared.

Harrison pleaded total ignorance about the circumstances surrounding

the theft. "I'm sure this happened during the move of course. We had

breakage and different things. So many hands were touching, but these

things can happen." he claimed National knew nothing else.

Yet, the question od whether the theft was an inside job was a sore

point. "I don't know. I can't say anything." snapped Harrison. "I

don't think it's an inside job, so i don't want to say anything at

all." But Harrison wasn't interested in saying too much about any

facet of the theft.

A national staffer we spoke to assured us that an inventory had been

taken. "Right after Sol found out, he had a complete inventory taken.

At first we thought thousands of pages were missing. We finally found

out that only 1928 pages were gone." Harrison vehemently denied that

he had taken an inventory. "We're in the process of taking inventory

right now. But we haven't done anything yet. We don't know how many

pages were taken yet."

Harrison's reluctance to address himself to the facts of the theft

even extended to a description of what was stolen. "We don't know yet

what was taken. We've left that up in the air at the moment. We'll

know after inventory comes in."

Harrison's production people disagreed, however. According to one

staff member, an exact listing of what was stolen has been in

circulation for several months. They think that the material will

never surface, however. "It's fantastic stuff," one artist said. "I'd

like to have some of the material for my own collection. People who

buy it may never sell it." Additionally, much of the stolen material

was romance pages which are not big sellers and never appear at

conventions anyway. [Inside Comics has uncovered a partial listing of

the stolen material. See inset elsewhere.]

Wanna Buy Some Hot Pictures?

After the skid of artwork was misplaced, the thief was forced to

unload the material quickly. And since there is no known comic fence,

he had to take his material to a convention. His first opportunity to

sell the artwork was at New York's August Comic Book marketplace.

Unfortunately, most of the city's biggest dealers were missing from

this particular fanclave. Scheduled only a week before the larger San

Diego convention, larger dealers like Phil Seuling, Al Schuster and

Bill Morse weren't in attendance.

"That was really a rough break for the seller," said a collector who

now owns some of the stolen material. "He was sitting there with 50-60

thousand dollars worth of stuff and the big guys were out of town."

What the thief eventually did was to unload the artwork at any price.

Carrying a few sample pages around the Hotel McAlpin's dealer's room

(one collector said two Adams detective coves and a Green lantern

Green Arrow page was among the batch), he struck a deal with a small

time comic art dealer working out of New Jersey.

Another collector who eventually bought several dozen pages of the

stolen art claimed that the dealer "Lacked the wherewithal to swing

the deal by himself and worked out a deal with a bigger new York

dealer." the New Jersey - New York combine bought the 1900 page stack

for about $5000. "A value that I would have loved any day." said one

New York City collector who heard the price. "Especially since the

stuff had to be worth ten or fifteen times what he got."

The dealer who subsequently bought the artwork may have been small,

but he was smart. Knowing National would probably try to trace the

art, he limited his sales. According to one purchaser, "this dealer

wouldn't sell to anyone for speculation purposes. he sold it only to

top-notch, highly reputable collectors. He knew that going to big

collectors meant the stuff would stand in the closet - in someone's

collection."

Another collector, who admitted to buying "only a page or two" of

stolen material, said that the dealer was "the most careful man I've

ever seen. He told me that he'd only sell the art if I put it in my

collection and didn't sell it. Even then he was cautious and looked

like he didn't trust me."

About a half dozen well known, highly respected collectors eventually

purchased the bulk of the choice material for about $20 a page. The

seller dumped the pages at this low price to minimize his risk. With

dozens of high quality, much desired Neal Adams and jack Kirby pages

in his possession, the dealer sold the pages at a lower-than-normal

price in exchange for a relative measure of security.

"Before he would even let me look at the stuff," a New Jersey

collector said, "I had to promise him that I'd keep the stuff for my

own collection. Then he brought out the Adams and Kirby and Wrightson

and Kaluta stuff. It was unbelievable the stuff he had. His prices

were really cheap. So i shut my mouth and bought about 30 pages."

Within a week of the August Comic Book Marketplace, most of the best

material was already sold. However, since he had a large amount of

neal Adams pages, he took the remaining material to the San Diego

Convention. Adams was the guest of honor at the annual fanclave and he

was sure he would do very well.

And while he did sell a goodly amount of the pages, had he not brought

the material to san Diego, national might have never discovered the

theft.

Better Late Than Never

One of the other guests at the San Diego convention was none other

than Sol Harrison. Even though several weeks had passed since the

material was purloined, Harrison was still unaware of the theft.

"Everything was incredibly hectic during the move," Harrison said. "I

was mainly concerned with the orderly transition of the office. Who

thought we would have such a chunk stolen?"

Harrison didn't find out about the theft until he happened to drop by

the convention's auction. On display for bidding was a Neal Adams

drawing for a House of Mystery cover.

Sol told me it was the first time he realized something was fishy,"

one of his assistance said later. "He just knew that page should have

been in the office. That's when Sol finally realized stuff was

missing."

returning to his office the next week, Harrison initiated an

inventory. he also called in a professional security team to

investigate the theft. "It just so happens that Warner Communications

now owns a security outfit," said Harrison, "and I had no qualms about

going to them. I told them, 'Listen, this stuff is missing, and we

want it all back'."

Unfortunately for Harrison and National, the security outfit turned up

very little. the dealer had been so careful in selling the material,

most of it was buried in private collections.

"The only way i am going to give up my stuff," said one collector, "is

if i die. And I am 27, so they've got a long wait."

Besides disclosing that 1928 pages were missing, the only other fact

the investigation turned up was a rough idea of the thefts date. While

almost everyone concerned agreed it came during the National move, no

one could do more than speculate. Luckily, one of the stolen stories

had been previously taken.

A Neal Adams story, "Snowbirds Don't Fly," had been lifted by one of

National's production people several months before. After publisher

Infantino discovered the theft, the staffer returned the material one

or two weeks before the National move. When the inventory was taken

after the 1900 page theft, however, the story was again missing, and

that set the theft right around the time of National's move.

One collector, a close friend of neal Adams, said the story was stolen

with the intention of returning it to Adams. It never reached Neal -

and he would have returned it if it did - and when it was returned to

National, "the collector said it was being held in special care."

We Want Our Material Back

After definitely establishing that the original art work was indeed

stolen, National's legal department drafted a letter Harrison said was

sent to any place "where art had touched base." The notice first

appeared in the sixth issue of Comicscene and later in the Comic

Reader #101. Captioned "An Important Notice From National

Periodicals." The letter read: "It has come to the Publisher's

attention that valuable original artwork representing fictional

characters of which Publisher is the copyright owner has been stolen

from the Publisher's archives and is currently being offered for sale.

PLEASE TAKE NOTICE that any person, firm or corporation who is found

to possess this artwork or is found selling or attempting to

distribute this artwork will be prosecuted to the full extent of the

Federal Copyright Act and all other applicable federal and state

statutes. Anyone with the knowledge of the whereabouts of this artwork

or the events leading to it's theft from the Publisher is urged to

contact Publisher immediately."

The letter was the first public notice about the theft of the artwork,

and Harrison was particularly disturbed by the cavalier attitude

toward the material. he constantly mentioned that National owned the

material and that they were "determined to secure it's return."

National was finished playing games.

"This is stolen merchandise," he said, his voice raising to a

falsetto. "I thin the industry has become very lax in their conception

of what a piece of artwork is. If you don't think of it in terms of a

piece of artwork, and think of it in terms of a piece of property,

you'll know it's a felony. I's stolen property."

He was insistent in his claim that National would take the case to

court. "If anyone peddles stolen property, he becomes accessory to

that felony. All I want people to understand is that we're going to

prosecute these people. We want to find out who did this. Someone

stole our property. " Harrison said again. "We want it back and we're

going to prosecute to get it."

There was never any doubt that the theft was a felony, but some

lawyers who've seen National's statement disagreed with it's thrust.

Alan M. Carson, consulting partner in the california law firm of

helmut, Kline and Stone, is copyright specialist and questioned the

letter's legal foundation. "it's certainly conceivable that the owner

could sign a complaint against the defendant for larceny and other

charges," Carson said, "But I really doubt they can prosecute under

the Federal Copyright Act."

Seymore C. Kline, also a copyright specialist in Helmut, Kline and

Stone, attacked the statement's validity from another legal

standpoint.

"It's rare - in fact, I can't cite an example - where one can

prosecute under the copyright law unless the copyright has truly been

infringed upon. Unless the defendant put the material into print, I

doubt the owner can sue under the federal Copyright Act."

Kline said that national had a strong case under larceny and theft

statutes, however. "The best line of prosecution, it seems to me, is

to try to prove that the defendant sold this material over the state

lines. Then it becomes a Federal offense - transporting stolen

merchandise over state borders."

Carson said that copyright laws are primarily "civil" statutes in most

states and rarely entail anything more than lawsuits. "You can sue on

federal copyright laws, but I doubt they could try to hang a theft on

him under copyright laws."

Harrison, on the other hand, said that the letter was a document

prepared by the company's lawyers. "That letter is a legal document.

Our legal department framed that letter and they know what it refers

to. They feel it's a violation of copyright. I'm not going to question

them on that."

*****

The theft also brought to a boil a question that had already been

simmering for some time. Some freelance artists were claiming that

national never owned the artwork in the first place. in the 22nd-23rd

issue of the ACBA Newsletter, the academy of Comic Book Arts took a

rare snipe at National: "If, as the Academy argues, the physical

artwork belongs to it's creators, then many artists have suffered a

grave injustice at the hands of [National] ... Return the artwork to

it's creators. Put aside storage charges, security systems, lack of

confidence in employees."

Neal Adams, much of whose work was among the stolen, and Howard

Chaykin have stated they will no longer work for national due to the

theft.

But Nationals main concern will remain with the artwork itself. they

have pressed their efforts to regain the stolen material. And they are

serious about prosecuting. According to one National staffer, "All you

hear is Sol and Carmine talk about how they'd like to get the bastards

who stole the stuff."

But, as several collectors who purchased pieces of the stolen material

have said, National has to find them first. And that's shaping up as a

task even Warner Communications vast network cannot handle.

You might even say that finding the thieves is a job for Superman

J David Spurlock: Thank you Patrick Ford for this good, work which is

of value to anyone researching the history and provenance of stolen

comic book art.

Steve Meyer: This is great, thank you for typing it up or scanning it.

Patrick Ford: Just an Internet search and then cut and paste.

Patrick Ford: I found it on an old internet forum. Someone had

transcribed it from the magazine.

Patrick Ford: This report and another article in TCJ which quotes

Robin Snyder casts doubt on the claim that DC routinely shredded

artwork. Unlike Marvel DC did give away artwork to fans, but I've seen

no good evidence that DC shredded original art.

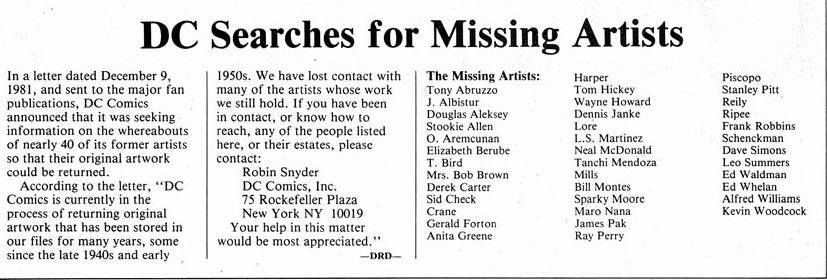

Patrick Ford: Here's a news story quoting Robin Snyder which ran in

THE COMICS JOURNAL #70 (Winter 1981-82).

Interestingly enough just days after noticing this ad while searching

through the digital TCJ Archive, I received the January 2016 issue of

THE COMICS. Robin Snyder describes in that issue his efforts to return

many thousands of pages of original art which DC had in it's

possession. The pages dated from the 1930s through the early 1970s.

Robin mentions that there were thousands of pages by Tony Abruzzo.

This information does not seem to jibe with the CBF "well known

historical fact" which says that in the '40s, '50s, and '60s DC

systematically destroyed almost all the original artwork which passed

into the company's hands.

Patrick Ford: http://boards.collectors-society.com/ubbthreads.php

So how did DC art "get out"? - Collectors Society Message Boards

Tim Bateman: Why would National destroy original artwork?

They needed it to make stats for overseas publishers, surely? (This

ties in with the lawyers' copyright concerns, if only tangentially).

Patrick Ford: Robin Snyder wrote there were Ed Wheelan pages dating to

the '30s. I believe the shredding story is a lie.

J David Spurlock: When DC moved their offices, Carmine Infantino was

out of town. Sol Harrison decided it was too much work to move all the

art and as they has negatives on much of it to reprint from, ordered

youngsters like Wolfman and Wein to cut up and trash pages. They did

some but "saved" some that they had carefully cut in half. When

Carmine got back and found out, he ordered no more cutting or trashing

of originals.

Patrick Ford: BRANCATELLI: "Except for several sharp eyed young staff

members. most of them, lower echelon employees, came up through the

fan ranks and knew the value of the unattended artwork."

Patrick Ford: David, That is the official story known by fans, but it

is contradicted by the Brancatelli article.

J David Spurlock: what i said about cutting art has nothing to do with

the separate heist -- i was just commenting on cutting/trashing of

art. Carmine said if there was any before the prep to move, he was

unaware of it.

Patrick Ford: The article says the art was all packed up to be moved

and that is when the theft occurred.

J David Spurlock: yes

Patrick Ford: It strikes me as highly unlikely that Harrison would

order artwork destroyed just prior to the move when that is the exact

opposite of what Harrison told Branacelli.

J David Spurlock: that was after Carmine said, no destroying of art

Patrick Ford: BRANC: According to one National staffer, "All you hear

is Sol and Carmine talk about how they'd like to get the bastards who

stole the stuff."

J David Spurlock: Sure, they were pissed

home