|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

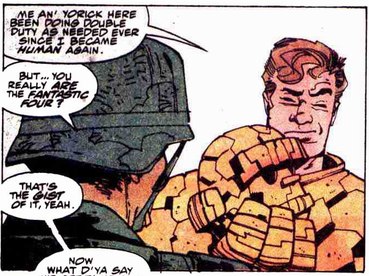

Above: Reed Richards' visual equivalent of "To Be Or Not To Be." See Act 4 of the Fantastic Four for context, and FF251 for this scene.

There are many parallels between Shakespeare and the Fantastic Four, particularly Hamlet. This includes the criticisms. Whatever you say against comics can be said against Shakespeare.

The main difference between the two is their different unique selling point. Shakespeare's unique selling point is his rich language, but that rich language also scares away new readers. The Fantastic Four's unique strength is its accessibility: it's a lot more fun.

Today, Shakespeare is considered the gold standard in high class literature. But it was not always so:

"Although generally popular in his day, these plays were frequently little esteemed by his educated contemporaries, who considered English plays of their own day to be only vulgar entertainment." - source

"Plays were considered ephemeral and somewhat disreputable entertainments rather than serious literature." - source

This sounds a bit like comic books in the twentieth century.

"With a few exceptions, Shakespeare did not invent the plots of his plays." - Britannica

This sounds a bit like comic books in the twentieth century: forever adapting and re-imagining old plots.

"Shakespeare's first period was one of experimentation. His early plays, unlike his more mature work, are characterized to a degree by wooden and superficial construction and verse. Some of the plays from the first period may be no more than -retouching of earlier works by others." - source

Even his greatest plays have their weak points. For examples, Iago (in Othello) is a two dimensional villain who even tells the audience of his villainy. Still in Othello, three days became a week because Shakespeare was not paying attention, then Desdemona's father's death is just announced out of the blue with no build up or commentary. Shakespeare is happy to use a bizarre deus ex machina whenever he has a plot hole to fill, as when Hamlet is leaving Denmark as a prisoner, Shakespeare can't think what to do next, so he just announces that the ship was captured by pirates who conveniently return Hamlet to Denmark. And all the female characters in Hamlet are weak, dependent on the men. The weaknesses and plot holes are legion, even in his greatest works, but we overlook these because Shakespeare's strengths are so wonderful.

Once again this sounds like the comic books.

Shakespeare uses stylized dialog: nobody really talks like that. Characters say just the right thing, in the cleverest way. Few writers can duplicate that, let alone ordinary people in real life. Also his characters often speak in rhyme or in iambic pentameter. But it's enjoyable so we allow it.

The Fantastic Four has its own style: it eschews cleverness for

clarity. The Fantastic Four conveys the maximum information in the

minimum space, and can be enjoyed by all ages and reading

abilities. Unlike Shakespeare it's instantly understandable by

anyone.

Why, then, is Shakespeare so revered? Because like Jack Kirby in comic art, and Stan Lee in comic editing, William Shakespeare was the best there ever was in his chosen field. Just look at Shakespeare's range, his ability to attract empathy, and his talent with clever phrases, and above all his layers of depth.

RangeUnlike many of his contemporaries, Shakespeare's characters have a wide range of emotions and experiences. This is like the best comic books. But comics have the possibility of greater range because they cover a much longer period, a bigger story, with input from more writers. For example, Hamlet moves between honor and suicide and madness within a single hour, but over the six thousand page story of Reed Richards we see honor and suicide and madness, and also true love and courage and weakness and integrity and deception and hope and fear and jealousy and pettiness and everything in between.

Empathy

Shakespeare's skill with words lets the audience feel great empathy with his characters. But this is only true to a limited extent, otherwise children would not have to be forced against their will to read his plays. Shakespeare uses complex language that is only accessible to his sixteenth century audience, or to those who take the time to learn his style. Here the best comics have a great advantage: by using the simplest language they have no difficulty in being understood. By using pictures they are even more accessible. And readers grow up with the characters month by month, seeing every detail of their lives, they are not just characters on a stage or on a page: they become friends.

Unique talents

Every work of genius is unique. That is what makes it genius and not merely pastiche. Shakespeare is unique in its use of clever language: nobody can turn a phrase like the Bard of Avon. Though possibly this is helped by the fact that the language was still new. Just a couple of hundred years earlier was Chaucer's time, and a very different kind of English. Since Shakespeare's time the language has expanded continually, and each new generation is less impressed by novel phrases. Shakespeare, or his contemporaries the translators of the King James Bible, could add dozens of memorable phrases to the language. By the 1900s even the greatest poet was unlikely to add more than one or two phrases to general usage.

The unique talent of the Fantastic Four was not in adding clever phrases, but in its epic scale: a six thousand page story that evolved over twenty seven years and became the backbone of "The Marvel Universe" - the largest connected story in the history of the world.

Layers of depth

Shakespeare is able to show conflicting layers, including layers the speaker may not himself recognize. For example, when Hamlet pretends to be mad the audience can wonder if he is really mad. Or when he debates suicide and does not know how he feels. Unfortunately, a play is limited in length, so Shakespeare has to hit us over the head with a soliloquy. It would be more subtle to show rather than tell. This is where the best comics have the advantage.

These layers are most clearly seen in the second half of the FF Act 4: all the main characters are in denial, and their behavior can be interpreted in different ways:When Reed Richards has his slow nervous breakdown he never has to stop and tell us: we can see it happening. And it is all the more powerful because Reed himself has no clue that it is happening. Hie visibly ages, he becomes more withdrawn, his language becomes cold and mechanical. Unlike the youthful Hamlet, Reed cannot afford to wallow in self pity. He must carry on. He tells himself that nothing has changed, but who is he trying to fool?

Reed's actions are the deepest tragedy because he refuses to admit even the possibility of weakness, and all he has ever done is what he thinks is for the best. He is never a cold hearted first-person killer like Hamlet (with Polonius), so the audience can feel the despair as he attempts suicide while refusing to admit that anything is wrong. The audience must also decide where he went wrong. When does he stop lying for "good" reasons (e.g. the end of issue 7) and begin withholding key information out of habit? When is a lie of omission a lie? When does believing he can do the impossible (e.g. his busy period against Galactus at the start of Act 4) become irrational? The audience must judge.

Meanwhile Sue's makeover is supposed to make her more powerful but instead is a cry of despair. She makes her face like a little girl, gives herself a narrow waist and big bust, uses more sexual body language and references and actively romances Reed. In claiming to be liberated she has lost control over her life. She insists on national TV that she is now in control, yet at that exact moment her neglected son is confused, lost, and attacking the rest of her family. She cannot see it but we can.

Ben does the same in Acts 2 and 3: we know he's intelligent and serious, but he acts the fool.It's the only way he can cope with being under Reed's control, yet he does not know how to escape or even if he wants to.

Johnny with Alicia is another example. He acts like a carefree womanizer, but has had relatively few girlfriends and they have all ended in failure. We know what he looks like when in love (with Crystal, and when Frankie left him), and his restrained act with Alicia fools nobody but himself. He has to constantly tell himself that he loves her.

In general, the whole team acts as if nothing is wrong because they deal with near-death every day. They cannot afford to show weakness to each other, as the fate of the world depends on them... or so Reed thinks. But here the others can see what we can see: by Act 4 there are many other superheroes, Reed does not have to push them so hard, but he can't see it.

The following parallels are only coincidence: nobody is

claiming that the Fantastic Four is based on Hamlet. However, the

Fantastic Four is so rich and deep that parallels naturally arise

with Shakespeare's greatest work.

There may be even more parallels with other plays, particularly The Tempest: Reed Richards is Prospero, the genius hero who nevertheless sometimes lies and treats others as children; both stories start with a wrecked ship; both feature super powers; both have exotic locations, Utopian dreams, conflict with opposing ideals; Ben is Caliban, etc. But Hamlet is Shakespeare's most famous and renowned play so let us proceed.

Both Hamlet and the Fantastic Four were written at a time of change and anxiety about the future. Hamlet was written in the final years of the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, who died childless, and the nation was concerned about its future. Similarly, the Fantastic Four began at the height of the Cold War, and reflected its nations fears of the time. On a more personal note, Hamlet was written soon after Shakespeare's child died, leading to a more restrained and reflective play. While we do not know if Stan Lee or Jack Kirby suffered a bereavement in 1961, in a Comics Journal interview Kirby tells of how he found Stan weeping at his desk at the failure his life's work. This may be hyperbole, but the company was at its lowest ebb when Kirby joined, having sacked almost all staff, and Stan took it very personally. In Origins Of Marvel Comics Stan tells how he was planning to leave comics, so decided for once to write a more realistic comic, the kind of thing an adult would enjoy reading.

Hamlet is Reed Richards: a thoughtful hero, often the slowest to act, but occasionally rash. The pressure is too much, and may drive him over the edge, but we are never quite sure of his mental state. Hamlet’s defining characteristics are his pain, his fear, and his self-conflict. He cannot think about his responsibility for killing Polonius, because if he did then he could not cope. Reed is the same. Even at his lowest point he acts as if it is just another day at the office: to admit that he represses his friends, saved Galactus, needlessly endangered his friends with is Negative Zone trip, etc., would be more than he could cope with.

The ghost of Hamlet's father is the spirit of single-mindedly

conquering the frontier: Hamlet's father was busy conquering

Norway and now demands revenge. Reed's father is similarly single

minded and expects Reed to be ruthless. Reed meets his father

through ghosts in the dust of the old American frontier. Hamlet's

father's voice speaks from the earth because he was denied his

rights. In the same way, Reed's father speaks from the dust.

Another parallel with the ghost of Hamlet's father is the

Over-Mind. Is this real, or a creation of Reed's desperate mind as

he sinks into madness?

Hamlet's father was denied his last rites and so exists under ground: his voice comes from the ground. In FF1, an unnamed worker tries to follow the American Dream by becoming qualified and working hard, but is unjustly denied any job. He ends up underground where he is obsessed with revenge. Just as the ghost makes Hamlet's companions swear, so the Fantastic Four swear, and the test of their oath comes from underground.

Claudius is the various would-be monarchs who threaten the state - most of the FF's early foes are monarchs or would-be monarchs.

Gertrude is the American people. (The symbolism of the nation as bride to the king comes from the Bible.) The people are ultimately innocent, but too easily led, too quick to follow the bad guy (as with Galactus' herald Gabriel) and too quick to be brainwashed and condemn the hero (see the various times when the public is turned against the FF: in issues 2, 7, etc.)

Ophelia is Sue Storm, Reed's girl: Innocent, loving simple beauty, yet condemned in a sexist way. Ophelia's drowning herself half way through the play is like Sue leaving the unloving Reed to join the Sub-Mariner (climaxing in issue 149) . The battle in her grave is echoed by Reed's struggle with the Sub-Mariner.

Polonius is Ben Grimm in his human form: the friend who did not quite trust Reed/Hamlet. Reed killed Ben's human form.

Laertes is Ben Grimm in his "Thing" form: enraged that his "father" (his human form) is killed. Ben, the man of action, is the foil for thoughtful Reed.

Fortinbras is Johnny Storm: the natural leader who, though nearby throughout the story, cannot take his rightful place until the others have gone. His rule will be more democratic: how else can Johnny control the more intelligent Crystal and more powerful Franklin?

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are other superheroes: friends of Reed, but sometimes they act against him.

The final duel is mirrored in FF 296 (Hamlet/Reed versus Laertes/Ben) and annual 20 (Hamlet/Reed versus Claudius/Doom). The poisoned chalice is to be forever busy with matters of leadership: Doom drinks this by his own scheme backfiring, and he is kept forever busy with Kristoff. The poisoned blade is Ben's unconscious hatred for Reed. When Ben finally confronts his hatred and forgives Reed (in 296) he is able to leave it behind. This allows Reed to finally pass on the reins of power to Ben, who will, once he has proved himself a leader, inevitably pass the crown to the true leader, Johnny/Fortinbras.Action or waiting:

Hamlet often postpones action until he has time to think. This is

Ben's constant refrain: he can't stand Reed's habit of waiting

round and holding back..He wants action!

Uncertainty:

How can anything be known for sure? This is the major theme with

Dr Doom. No matter what you do he comes back somehow. Reed has to

accept that he will never be beaten, and instead be happy to keep

him busy (through Latveria and Kristoff). Reed's final dilemma is

on whether to interfere with Ben's new team, and he finally learns

(via Sue and Franklin) to leave Ben alone.

"To be or not to be..."

Reed tries to be everything, to solve every problem, and he fails.

This takes his reason for living, and his Negative Zone adventure

(251-256) can be seen as a suicide attempt. Or not: it is left for

the reader to decide. Meanwhile, Ben's life is a quest for

identity (man or monster?).

"Whether tis nobler..."

Reed, once he has decided, always rushes in. But Sue is aware of

the danger and provides he counterpoint "be careful, Reed!" and

offers a different solution: don't fight Namor, or the Dragon man,

or the Mole Man, or Gorr, etc., befriend them. There is a third

way.

Death and aging:

Reed's confidence is reflected in his health: from collapsing more

than once at the start of act four, to his haggard look at the

end. He finally lost his confidence when unable to defeat the

Skrull aging ray. Reed's desire to conquer all frontiers naturally

suggests conquering death, represented by the Negative Zone that

sucks in everything, and is ruled by "the living death" Annihilus.

Franklin stretches time specifically to avoid aging and death.

Madness:

Reed, the rational one, acts irrationally toward the end: is he

mad, or merely calculating badly? E.g. his Negative Zone trip, not

wishing to save Franklin, saving Galactus, helping Doom, etc.

Throughout the bigger story we see elements of madness: the Mad

Thinker and Maximus the Mad are mirrors of Reed, and the Over-mind

arc pushes Reed into madness. Another madness parallel is the

various doppelgangers: e.g. Sue knows that the Reed from counter

Earth is no her Reed because of his strange behavior.

Suicide:

The extended exploration of the Negative Zone can be interpreted

as Reed's death wish, but it is left for the reader to judge. Ben

sometimes reveals the view that his life is worthless, and so he

fights on even when death seems inevitable. This suicide theme is

made explicit when Ms Marvel tries to kill herself. she lets Ben

see himself from the outside, and helps them both to finally kill

their inner demons.

Incestuous Desire

Claudius marries his brother's wife. Laertes speaks of his sister

Ophelia with sexual imagery. Hamlet seems preoccupied with his

mother's sex life with Claudius. This undercurrent of incestuous

desire reflects the instability at the core of the story. The same

is true in the FF. Alicia enters the story because she looks

exactly like Sue, and at his lowest point Johnny convinces himself

that he loves her, and marries his sister's lookalike.

Misogyny

Hamlet's dismissive attitude to women ("get thee to a nunnery" and

"Frailty, thy name is woman") could have come straight from Reed's

mouth. One way to reed the FF is as the story of feminism: Reed is

dragged metaphorically kicking and screaming to admit that, yes,

Sue was always his equal. To a lesser extent Johnny learns Reed's

sexism: note the times when he would sit and relax while the women

cook and clean. This misogyny lost him his true love, as he

refused to make the sacrifices that Crystal made for him, and

never thought about her except when it suited him. He needed to

face his failures and marry the more mature Alicia to conquer his

sexism.

The skull

Hamlet sees the skull of Yorick and reflects on the past. By doing

so it draws attention to the other side, his troubled present. The

first issue of the FF takes us to Monster Isle, in the shape of a

monstrous skull - modeled on Skull Island in King Kong. Ben's

rocky, ear-less head is like a skull, and he often looks back

longingly to his human days. Near the start of the FF, in the

first annual, Namor (in disguise) brings a Homo Mermanus skull to

the United Nations as a test: will humans recognize their links

and act humanely to his people? Reed is impatient and the humans

fail the test. later, Reed's apparent greatest triumph (the false

dawn of FF200) ends with a statue of Doom crumbling with time,

like Yorick's skull. Kirby's last ever story (partly used for

FF108 but not fully published until after the big story ended)

revolves around the discovery of an ancient stone head with two

faces. As in Hamlet it is a focus for mankind's good and evil

sides.

Etc., etc.

As noted at the start, nobody is claiming that the FF is based on

Hamlet. Similar parallels could be found with Romeo and Juliet

(Johnny and Crystal), A Midsummer Night's Dream (Johnny and Ben

temporarily end up with the wrong partner), or any of

Shakespeare's plays. The number of parallels merely show that the

FF is a rich seam of fiction to be mined, both by academics and by

any reader who enjoys a multi-layered and fulfilling story.

Thanks to royal patronage, scholars paid attention to Shakespeare from the start. Given the high quality of his work, his reputation grew exponentially. Sadly this has not been the case for the Fantastic Four: it has been largely ignored, except among aging comic fans who recognize the early run by Kirby and Lee as the gold standard for comic books.

Worse, and perhaps fatally, the Fantastic Four story was abandoned by its publisher, Marvel. Continuity ended abruptly with issue 321. The numbering continued, fatally diluting the brand. It is as if Shakespeare produced dozens of sequels to Romeo and Juliet, where they come back from the dead and the Montagues and Capulets fight with ever more absurd super powers. There are now generations of comic readers who have no idea why the Fantastic Four was once revered.

However, there is cause for optimism. Thanks to digital technology it is now easier than ever to recover the past. As digital copies become more common it is hoped that more academics will have access to the first 321 issues of the Fantastic Four, and the story can finally begin to attract the scholarly attention it deserves.

Galactus and God

Jack Kirby: “When I created the Silver Surfer and Galactus it

came out of a Biblical feeling. I couldn’t get gangsters to

compete with all these superheroes, so I had to look for more

omnipotent characters. I came up with what I thought was God in

Galactus; a God-like character. Still thinking about it in the

Biblical sense, I began to think of a fallen angel, and the fallen

angel was the Silver Surfer. In the story, Galactus confines him

to the Earth, just like the fallen angel. So you can get

characters from Biblical feelings.” - quoted in Mark Alexander,

"Lee & Kirby: The Wonder Years"

The Bible and act 4

In their final most hopeless period, the end of Byrne's run at

the end of Act 4, these imaginative, optimistic pseudo-Biblical

quotes are replaced with more sober straight quotes from lesser

writers. The final triumph in Act 5 returns to the Biblical motif.

For example:

The cover to 316 "that which is forbidden" is an allusion to the fruit of the tree of knowledge in the garden of Eden at the start of Genesis: this issue begins with Johnny reunited with Alicia and promising himself that he will not take the forbidden fruit - Crystal. It ends with the forbidden fruit of knowledge of the 'gods' - the Beyonder).

The cover to 317: "the beginning and the end" is the title Christ gives himself at the start of the Book of Revelation. Like so many titles, it applies in a small way to the individual issue, but also in a much bigger way to the big story as a whole.

In 319 the Biblical parallels are made explicit: the Beyonder

wants to be a god, with his own Bible, his own Koran. But in

reality his self belief is vain: he is not the one above all

as he thinks.

He is merely a part of something broken, and the other part is

the socially inadequate Owen Reece. Similarly Doom sees

himself as equal to the Beyonder but is in fact a broken man

(he is incomplete) who is needs power in a bad way. Both are

given final peace, through a cosmic cube (a reminder of the

cubic heavenly city with walls made of jewels, in Revelation).

In 320: the story title is "pride goeth..." quoting "pride goeth before a fall" from the book of Proverbs. Again this applies both to the issue in question (the overconfident Hulk) and the series as whole: the editors in the post-Shooter period see their role as preserving their precious, the character they have inherited. They are intensely proud of these characters and will not let them change. Sadly, change is exactly that made these characters great, and the end of change means the end of greatness. The next issue, the end of this two issue arc, is where corporate pride takes over, and Marvel Universe falls.

Finally, issue 321 is titled: "After The Fall" - the perfect title for the last in-continuity issue. It applies both to this issue (after the defeat of the Hulk) and also the following twenty years in the wilderness, a comic without direction, harking back constantly to its lost glories.

Please note that the Fantastic Four is not consciously based on the Bible. Few of the parallels are precise. But they are parallels we should expect, given the novel's origins and its epic scope as the story of a family that represents a nation.

Issue 2 is like the rest of the book of Genesis, with the family (not yet a nation) in danger of losing its identity to more powerful foreign nations. The team being framed as evil is like Joseph being framed by his brothers and by Potiphar's wife. Again, the parallels are not exact: this issue is more closely based on cold war fear of communist infiltrators and Invasion of the Body Snatchers, but the epic scope means these are eternal themes.

Issue 3 is the start of the book of Exodus, where they leave Central City and establish a home in the center of New York. The Miracle Man (a reminder of Moses in the exodus) turns out to be a false miracle worker, like Pharaoh's priests; his exhortations to the infant team to give up based on his superior power is like Israel's murmuring in the wilderness, believing in the fleshpots of Egypt: the Israelites are led by a pillar of fire (like the Torch) and the light of truth vanquishes the illusion. Yea, I admit it, I'm stretching here, but the concepts in the comic are profound: confidence, illusion, and a bright light making us see error.

Issues 4 and 5 are like the rest of the Pentateuch, where the chosen family must deal with the monarchs of surrounding nations (Namor is a monarch, Doom is a would-be monarch at this point). This is when they establish their laws: these are the issues where both Ben and Johnny both try to leave, but come back because life under Reed is the right way..

Act 2 is the rest of the Torah

Planet X experiences a flood and the people escape in an ark; the chosen people are threatened by various surrounding monarchs and would-be monarchs (reminding us of the threat from Assyria and Babylon and Egypt) and internal division (reminding us of the division of the kingdom under Solomon's sons). The defeat by the Frightful Four and subsequent loss of power is the FF's equivalent of the Babylonian Captivity; Medusa's subsequent repentance parallels Nineveh, and so on. Sometimes characters are plucked straight from the Bible: the giant Watchers are straight from the book of Enoch.

Act 3 and the New Testament

Act 3 has the wedding (the Biblical metaphor for God and his church), then the Silver Surfer (often identified as a Christ figure), followed by the team's triumphant journeys through the world, just as Paul and the apostles journeyed through their world.

Act 4 and the trials of Christendom

Act 4 would be the long and difficult period of the next two thousand years, when things did not go as happily as planned.

Act 5 and Revelation

Act 5 then is the Book of Revelation, where the themes from Genesis return and are fulfilled, bringing the defeat if the anti-Christ (represented by Doom, the one who defeated the surfer), and then ends with indications of a future new heaven and a new earth, with the old Earth cleansed by fire and the new Earth being a sea of fire with a city with walls of crystal - like the team led by the Human Torch and his bride the Elemental being Crystal.

Appropriately, issue 321 finishes with a rogue Watcher: those

enigmatic beings from the apocalypse of Enoch, the fallen angels.

And apocalyptically he is is aided by a dragon, man.

The suspicious reader may think that the Fantastic Four could find parallels in anything, and so the parallels prove nothing. But it is nothing like the Greek plays, for example. Greek plays are the model for TV soap opera, with their unity of time and place (most take place around the same location within a short time), and where a character will enter a room and tell you exactly what she thinks. In contrast, the Fantastic Four, on its largest scale, operates on a huge canvas, and employs the unreliable narrator principle: for example, at the end of Act 4, Reed Richards pretends that all is well, but this is impossible to believe if we recall what has happened. Also his behavior (such as abandoning his child and taking his family, in effect, to hell) makes no sense unless he is unconsciously in despair. We can see things that Reed cannot. So the Fantastic Four is more like a Greek epic, combined with Greek myth, combined with a psychological study. It does not parallel everything, but only certain specific genres.

Conclusion

The Fantastic Four loosely parallels the Bible. It is not based on the Bible, but it is a national epic, a story of the development and spread of a family, and so is the Bible. So naturally there will be parallels: a dramatic origin, an expansion period, problems along the way, etc. The Fantastic Four is based on America, and America is heavily influenced by the Bible, so those parallels will tend to be close.

Does this mean the Fantastic Four must be dismissed as merely

derivative? Only if we also dismiss every epic text as derivative:

most of the ideas in the New Testament are also in the Old

Testament, and most of the ideas in the Old Testament are also in

Babylonian an Sumerian texts. The power of an epic is precisely

that it is not original: it sums up a whole nation of influences,

and does so in a single narrative, in a huge and unforgettable

way.