AnswersAnswers.com

Consciousness, and life beyond life

You are a point in space. This is what space feels like.

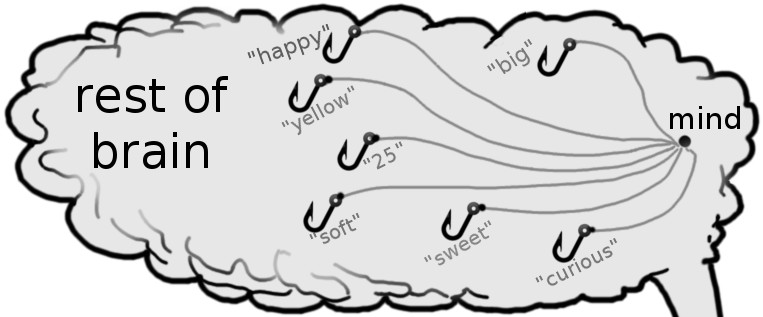

What is the mind?

The mind is where we make decisions for the whole body. The brain feeds information to the mind. But does it do so in large chunks? Or small chunks? And if so, how small? To find out, here is a puzzle: how many people in this photo are not wearing glasses?

(image: William Murphy, via Wikipedia, CC 2.0)

Did you know instantly? If not, then you must only see a little bit at a time, and only think you see it all at once. Plenty of experiments show that we actually see far less than we think. For example, if a computer tracks your eyes on a screen of text, it can hide everything except what you are looking at: changing everything else to "XXXXX". Yet the reader believes that they see everything.

(image: William Murphy, via Wikipedia, CC 2.0)

Did you know instantly? If not, then you must only see a little bit at a time, and only think you see it all at once. Plenty of experiments show that we actually see far less than we think. For example, if a computer tracks your eyes on a screen of text, it can hide everything except what you are looking at: changing everything else to "XXXXX". Yet the reader believes that they see everything.

So seeing everything is merely a belief: we actually see just one part at a time. For this and similar experiments, see Nick Chater's book "The Mind is Flat". So how much do we see at once? We might think we see a whole word or a whole shape, but do we?

So seeing everything is merely a belief: we actually see just one part at a time. For this and similar experiments, see Nick Chater's book "The Mind is Flat". So how much do we see at once? We might think we see a whole word or a whole shape, but do we?

How much can you understand in 1/40 second?

The mind can process forty pieces of information per second (see below). Yet it might take half a second to recognise an image. This suggests that when we see a word or shape we are really seeing lots of separate parts, faster than we realise.

The number forty comes from thinking about language. Our brains are highly optimised for language, and no matter what the language we all process about 40 bits of data per second (actually 39.15).This happens to be the optimal brainwave frequency (the "gamma wave"). Why do brainwaves have a frequency? Because conscious thought often has to access many parts of the brain: memory, multiple senses, speech, etc. But the brain uses electrical signals. It cannot risk signals from one idea interfering with signals for the next idea. So the brain regulates itself in pulses of one idea at a time. Even if we did not have the speech evidence and gamma evidence and electrical evidence, direct experience tells us that a complex idea will take longer to process than a simple idea, implying that we do not process ideas all at once.

So the mind only contains enough data to form an extremely simple shape, or extremely simple emotion. Plus the idea that "yes this connects to something else." How much data is that?

The number forty comes from thinking about language. Our brains are highly optimised for language, and no matter what the language we all process about 40 bits of data per second (actually 39.15).This happens to be the optimal brainwave frequency (the "gamma wave"). Why do brainwaves have a frequency? Because conscious thought often has to access many parts of the brain: memory, multiple senses, speech, etc. But the brain uses electrical signals. It cannot risk signals from one idea interfering with signals for the next idea. So the brain regulates itself in pulses of one idea at a time. Even if we did not have the speech evidence and gamma evidence and electrical evidence, direct experience tells us that a complex idea will take longer to process than a simple idea, implying that we do not process ideas all at once.

So the mind only contains enough data to form an extremely simple shape, or extremely simple emotion. Plus the idea that "yes this connects to something else." How much data is that?

The ten variable mind

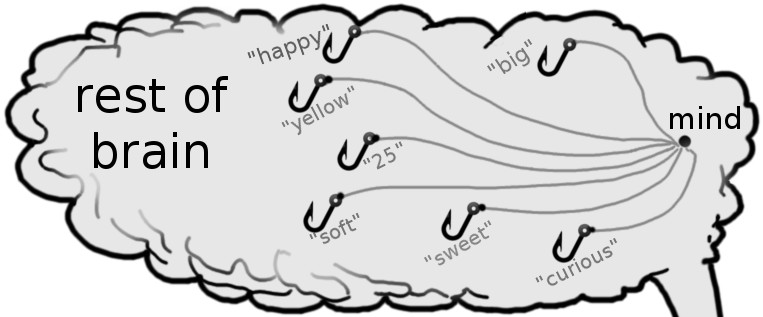

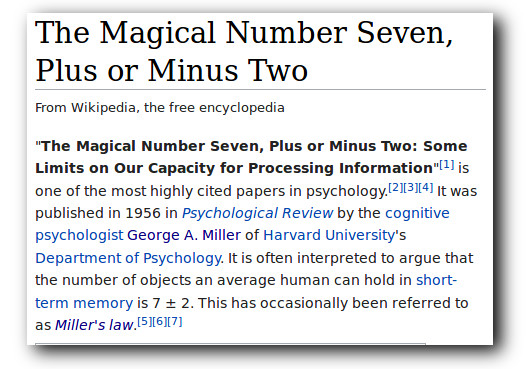

Let us dig deeper into the mind. You might notice that you can only remember around seven or so ideas at one time.

Of course you can always learn to link ideas together, and use one idea to pull another from memory. Memory experts can use this method to pull enormously large amounts from memory. But this method always had a tiny delay, because the ideas are not all in the mind at one time. This suggests that at each moment the mind contains just ten hooks: ten references to other neurons.

Of course you can always learn to link ideas together, and use one idea to pull another from memory. Memory experts can use this method to pull enormously large amounts from memory. But this method always had a tiny delay, because the ideas are not all in the mind at one time. This suggests that at each moment the mind contains just ten hooks: ten references to other neurons.

With training we can remember as many as nine items at once, which suggests an upper limit of maybe nine. Presumably the brain needs an extra slot free (so it is not completely oblivious to the rest of reality in case a tiger attacks), so this suggests that the mind contains about ten variables (changing up to forty times per second).

If the memory expert is distracted, for example by a tiger attack, those hooks are repurposed. This is how digital computer memory works: a series of 1s and 0s are enough to encode every kind of information. That information is constantly shuffled around in working memory, and often compressed so the space normally reserved for one big number can be used for three or four small numbers. Billions of years of evolution mean that brains are vastly more efficient than digital computers, so they must be doing this shuffling and repurposing all the time.

The point of all this? Everything we experience in one fortieth of a second can easily be contained within ten numbers.

With training we can remember as many as nine items at once, which suggests an upper limit of maybe nine. Presumably the brain needs an extra slot free (so it is not completely oblivious to the rest of reality in case a tiger attacks), so this suggests that the mind contains about ten variables (changing up to forty times per second).

If the memory expert is distracted, for example by a tiger attack, those hooks are repurposed. This is how digital computer memory works: a series of 1s and 0s are enough to encode every kind of information. That information is constantly shuffled around in working memory, and often compressed so the space normally reserved for one big number can be used for three or four small numbers. Billions of years of evolution mean that brains are vastly more efficient than digital computers, so they must be doing this shuffling and repurposing all the time.

The point of all this? Everything we experience in one fortieth of a second can easily be contained within ten numbers.

What information is in a number?

What are numbers, anyway? For example, what is the number 3? Well it is more than 2. Which is more than 1. So the number 3 contains information: that it contains lesser numbers in a line. 3 contains information, just as your mind contains information, So 3 is a kind of primitive mind.

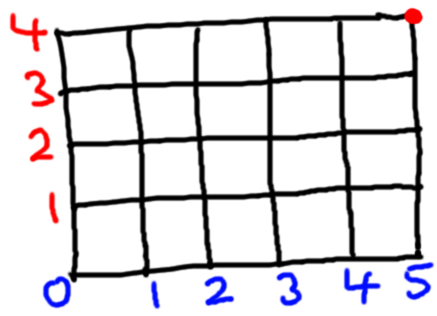

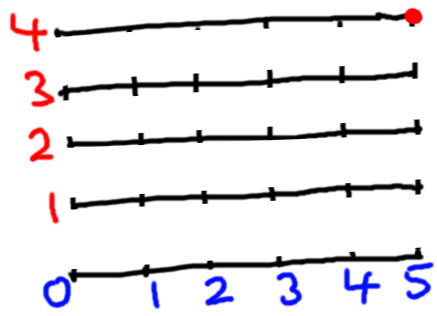

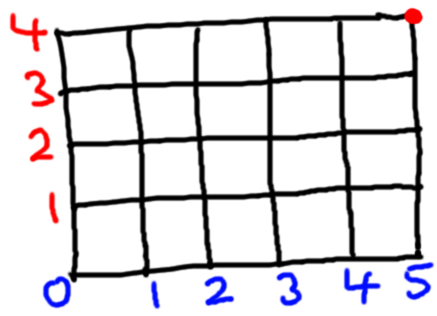

What about a point in 2 dimensional space? Like this point, (4,5)?

As you can see, it contains the information "4 lots of 5".

As you can see, it contains the information "4 lots of 5".

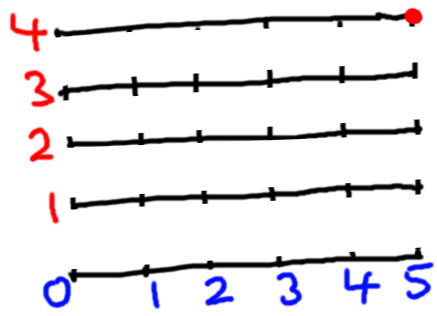

In other words, 4 waves, each of wavelength 5. So this primitive mind contains primitive waves!

In other words, 4 waves, each of wavelength 5. So this primitive mind contains primitive waves!

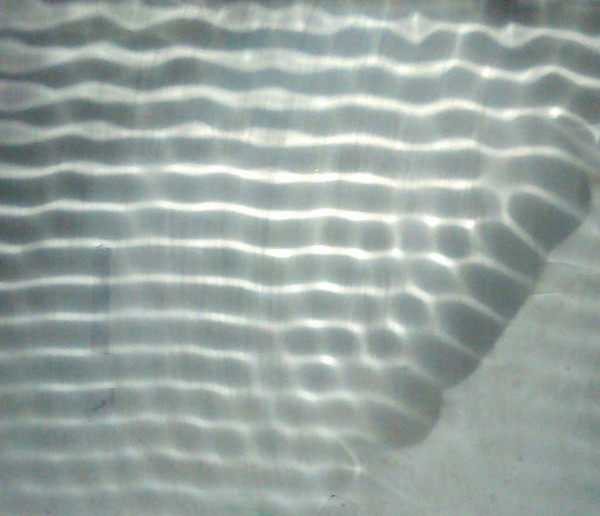

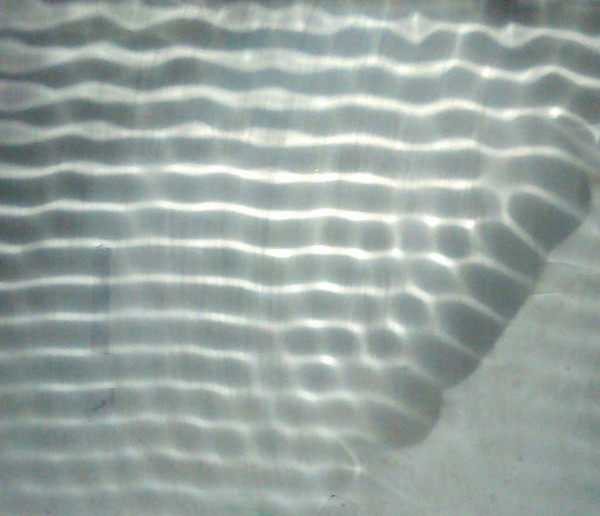

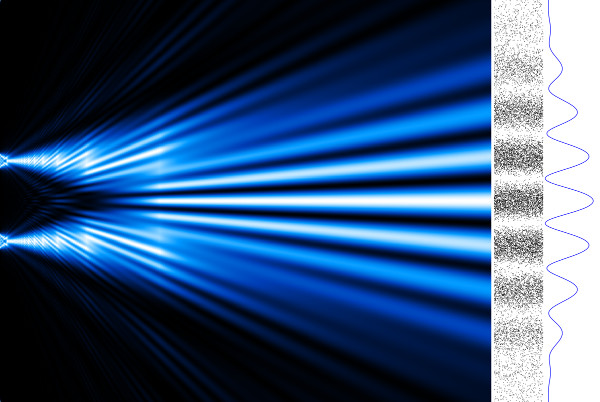

(image: Psgs123xyz, via wikipedia, CC0 1.0)

Why does this matter? Because all physics is made of waves. The colour "red" for example is just waves separated by about 700 nanometres. Or in other words 4.3x10^28 planck lengths. A planck length is the fundamental unit of distance in the universe, Being fundamental it is really just a number - whatever we call it only for convenience so we don't mix it up with other numbers. All of physics is like that: just numbers forming waves. The more numbers we have, the more sophisticated ad interesting a point in space might be. We have seen that one number contains information, so is a kind of very primitive mind. Two numbers together contain a very primitive waves, a kind of super-basic knowledge of colour.

Let that idea sink in! Every point in the universe is a mind that knows the concept of colour, or something equivalent.

With three numbers we could add even more richness and detail.

(image: Psgs123xyz, via wikipedia, CC0 1.0)

Why does this matter? Because all physics is made of waves. The colour "red" for example is just waves separated by about 700 nanometres. Or in other words 4.3x10^28 planck lengths. A planck length is the fundamental unit of distance in the universe, Being fundamental it is really just a number - whatever we call it only for convenience so we don't mix it up with other numbers. All of physics is like that: just numbers forming waves. The more numbers we have, the more sophisticated ad interesting a point in space might be. We have seen that one number contains information, so is a kind of very primitive mind. Two numbers together contain a very primitive waves, a kind of super-basic knowledge of colour.

Let that idea sink in! Every point in the universe is a mind that knows the concept of colour, or something equivalent.

With three numbers we could add even more richness and detail.

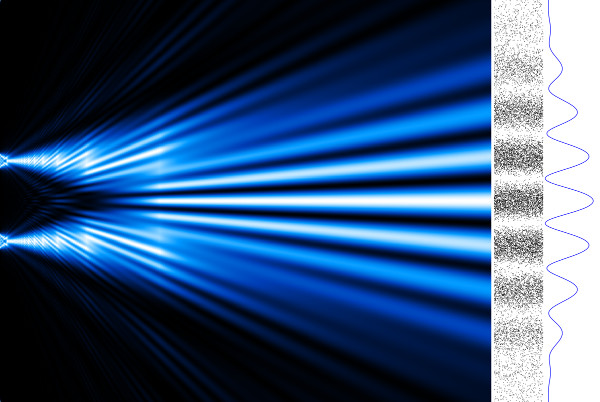

(image: Alexandre Gondran, via wikipedia, CC4.0)

Every point in space exists in at least four dimensions, when we include time. Imagine how much wave information could be encoded in a four dimensional number. Or even five.

(image: Alexandre Gondran, via wikipedia, CC4.0)

Every point in space exists in at least four dimensions, when we include time. Imagine how much wave information could be encoded in a four dimensional number. Or even five.

(image: Fractal Bargain Bin)

According to String theory, there are ten or even eleven dimensions. That's plenty of space for everything we could possibly think about in one fortieth of a second.

(image: Fractal Bargain Bin)

According to String theory, there are ten or even eleven dimensions. That's plenty of space for everything we could possibly think about in one fortieth of a second.

(image: Fractal Bargain Bin)

Or perhaps the holographic universe theory is correct and there are really just two space dimensions plus time. Remember that while we might think we see colours, but really we see frequencies. It may be that one dimension is the kind of thing we see (colour, shape, happiness, or the belief that we see everything), and the other dimension is which thing we see (which frequency, which shape, how happy, how much we believe that we see it all, etc.). But ten dimensions are easier to visualise, because we think we can visualise ten shapes at once. Even though really we can't.

(image: Fractal Bargain Bin)

Or perhaps the holographic universe theory is correct and there are really just two space dimensions plus time. Remember that while we might think we see colours, but really we see frequencies. It may be that one dimension is the kind of thing we see (colour, shape, happiness, or the belief that we see everything), and the other dimension is which thing we see (which frequency, which shape, how happy, how much we believe that we see it all, etc.). But ten dimensions are easier to visualise, because we think we can visualise ten shapes at once. Even though really we can't.

Can a point in space make decisions?

The brain feeds ideas to the mind so it can make "yes" or "no" decisions. How can a point in space make a decision? To answer that, we need to understand how decisions are made.

Question: if an outside observer knew everything about you, could they predict your decisions? If the observer can predict then you have no freedom to change it. But if you have freedom to change it then you are not predictable. That is, you are random, because if you were not random then you would be predictable, by definition. So the states of a subatomic particle - its position, its waves, etc - are decided in exactly the same way that you or I decide things. Each decision is either forced on us by outside influences, or it is random. A decision cannot be anything else.

We will now look at several proofs that the mind has to be a point in space. These will lead to an understanding of happiness, memory, friendship, and the other things that define your personality.

Proof 1: Occam's razor

Occam's razor says she should shave off unnecessary details. If the mind could be explained by a thousand points in space, or it could be explained by just one, then we should go with the "just one". (It might be tempting to say "why even ask the question? Why not say 'I don't know' and that only takes zero points in space!" But that does not explain anything.)

Proof 2: can you be in two places at once?

Can you be in two places at once? If so, then a thing would "be" on one position and "not be" in that position at the same time.

That is impossible, by definition. So it must be true for the brain as well. This becomes obvious when we think of what consciousness is. Consciousness is where we make the brain's highest level decisions. There can only be one highest level, otherwise we risk disagreement.

That is impossible, by definition. So it must be true for the brain as well. This becomes obvious when we think of what consciousness is. Consciousness is where we make the brain's highest level decisions. There can only be one highest level, otherwise we risk disagreement.

This has to be true right down to the subatomic level. Therefore consciousness must be a point in space. It cannot be a system of many points. (Invoking Heisenberg's uncertainty principle does not help: the principle proves there is uncertainty, not logical contradictions.)

This has to be true right down to the subatomic level. Therefore consciousness must be a point in space. It cannot be a system of many points. (Invoking Heisenberg's uncertainty principle does not help: the principle proves there is uncertainty, not logical contradictions.)

Proof 3: is magic real?

Some people say that properties can emerge from nowhere. This is called emergence. They say that consciousness emerges from atoms even though it does not exist in atoms. In other words, a thing appears that did not exist before. In other words, it is magic: like producing a rabbit from a hat. But in reality the rabbit was always in the hat. This is true of all emergent properties: they already exist in their component parts. To see why, consider the nature of subatomic particles.

Everything is made from subatomic particle. Every subatomic particle follows Heisenberg's uncertainty principle: it could be at any position and velocity. So a particle can be every part of a rabbit. That is, every point in the shape of a rabbit is contained within a single particle. That particle also contains every point in a teapot, every point in a planet, and so on. By combining particles together we do not create a rabbit, we simply remove all the non-rabbits.

Take a snowflake for example. Wikipedia states: "The formation of complex symmetrical and fractal patterns in snowflakes exemplifies emergence in a physical system." But where did this complex symmetrical and fractal pattern come from? It is implied by the mathematical shapes of the molecules, which are in turn implied by the mathematics of reality. Mathematics is all symmetry and fractals. For the snowflake to exist, we merely select one of the infinite number of existing mathematical arrangements.

All choices create happiness (even if very brief and very slight)

You always choose the thing you think makes you happy, by definition. So all choices create happiness in the moment they are chosen. It may not be MUCH happiness, and one second later you might become conscious of "oh no, why did I do that?" but in the moment of choice, happiness has to increase by at least a tiny amount for at least a split second.

Choices and happiness are the same thing

There is no reason for the brain to create happiness: its survival depends on good choices, not happiness a such. So happiness must be a natural result of choices. But a choice is the simplest possible state of matter: a simple "is" or "is not". So there is literally no space for happiness being separate from choices. So choices and a happiness must be the same thing.

The brain reduces choice

The brain needs precise choices. So it must provide precise inputs to the mind. So it must limits the choices the mind can make. So your brain limits your happiness. For example, you cannot choose to just do nothing: you must go to work, face problems, etc.

"Objection: an electron inside a rock doesn't have much choice either!"

Statistically, all choices - that is, all probabilities - are centred around zero. So while an electron around an atom might jump anywhere in the universe, it is 99.999 percent certain to be near its atom. So it makes no difference to that electron whether there are other atoms nearby. it can happily do its own thing, and only once every billion billion times will other electrons say "no, sorry, you can't do that Dave". Compare that to a human mind. Pretty much everything we want to do is "Sorry, can't stay in bed. Sorry, you can't fly. Sorry, you can't stop that pain."

(Waves and particles:)

(Why talk about electrons? An electron is a particle. That is, a wave in overlapping fields called charge, mass, etc. That is, a series of fluctuations in a point in space. We study those fluctuations across different points in space at different times and call the resulting pattern of waves a particle. But that is just shorthand: really only points in space exist with dimensions like X position Y position, Z position, charge, mass, spin etc.)

A random point in space knows more than you

We like to think of our large brains as letting us understand reality. Yet in reality they insulate us from reality. True, the brain contains information, but it contains a lot less than is in the wider world. The smaller the brain, the more you get your data direct from the outside world. And the brain is only interested in its own survival: there is little survival value in letting the mind gaze at the stars when it could be killing enemies and earning money.

A random point in space has more friends than you

All the mind experiences is happiness (in its ten different dimensions). So when we experience friends, it is just those ten happinesses being increased by those around us. But how many people actually make you happier? Ten? A hundred? Compare a random point in space: all of the billions of points around it present choices, and those choices are 99.999 percent good. So the random point in space has billions of friends.

A random point in space has more memories than you

Memory is information that reveals the past. Everything that exists contains some information about the past, because it exists in time. For example, if a random particle in space is knocked by another particle, then it will move. That movement is information about the collision: it is a memory. When we examine the charge, mass, spin, etc. of a point in space we are examining memories of everything that ever happened to that position. If we examine it across time we will see waves of change that physicists call fields and particles. Study that point in space for long enough and you can deduce everything about all possible universes, and a great deal about this particular one, right back to the big bang. That is, it contains those memories. But if that point is space is a human mind then it is constantly harassed by the brain and cannot remember anything before it was a baby.

A random point in space lives forever

When you die you experience different memories of course. But this is normal: our memories change throughout life. Death is just a bigger change: a change to a better existence with better memories.

We live in denial

We have seen that random points in space are happier, know more, remember more, and have more friends. In contrast, a mind is just the focus of all the brain's problems. The brain is a very fragile and unlikely thing, so it has a lot of problems. Yet it tells the mind that being enslaved by a brain is a good thing! The brain has to tell us this so it can survive, just as citizens of North Korea are told that they live in the best nation on Earth.

(image copyright K C Green, Okayed for social media - does this count?)

(image copyright K C Green, Okayed for social media - does this count?)

The dead come back to tell us

Random points in space form 99.9999... percent of the universe. They speak to us in the universal language of logic: they say "we are matter like you! Except we don't have a brain giving us endless problems! We know more, remember more, experience more, have more friends, more choices, and are much happier than you!"

Will we listen?

AnswersAnswers.com

(image: William Murphy, via Wikipedia, CC 2.0)

Did you know instantly? If not, then you must only see a little bit at a time, and only think you see it all at once. Plenty of experiments show that we actually see far less than we think. For example, if a computer tracks your eyes on a screen of text, it can hide everything except what you are looking at: changing everything else to "XXXXX". Yet the reader believes that they see everything.

(image: William Murphy, via Wikipedia, CC 2.0)

Did you know instantly? If not, then you must only see a little bit at a time, and only think you see it all at once. Plenty of experiments show that we actually see far less than we think. For example, if a computer tracks your eyes on a screen of text, it can hide everything except what you are looking at: changing everything else to "XXXXX". Yet the reader believes that they see everything.

The number forty comes from thinking about language. Our brains are highly optimised for language, and no matter what the language we all process about 40 bits of data per second (actually 39.15).This happens to be the optimal brainwave frequency (the "gamma wave"). Why do brainwaves have a frequency? Because conscious thought often has to access many parts of the brain: memory, multiple senses, speech, etc. But the brain uses electrical signals. It cannot risk signals from one idea interfering with signals for the next idea. So the brain regulates itself in pulses of one idea at a time. Even if we did not have the speech evidence and gamma evidence and electrical evidence, direct experience tells us that a complex idea will take longer to process than a simple idea, implying that we do not process ideas all at once.

So the mind only contains enough data to form an extremely simple shape, or extremely simple emotion. Plus the idea that "yes this connects to something else." How much data is that?

The number forty comes from thinking about language. Our brains are highly optimised for language, and no matter what the language we all process about 40 bits of data per second (actually 39.15).This happens to be the optimal brainwave frequency (the "gamma wave"). Why do brainwaves have a frequency? Because conscious thought often has to access many parts of the brain: memory, multiple senses, speech, etc. But the brain uses electrical signals. It cannot risk signals from one idea interfering with signals for the next idea. So the brain regulates itself in pulses of one idea at a time. Even if we did not have the speech evidence and gamma evidence and electrical evidence, direct experience tells us that a complex idea will take longer to process than a simple idea, implying that we do not process ideas all at once.

So the mind only contains enough data to form an extremely simple shape, or extremely simple emotion. Plus the idea that "yes this connects to something else." How much data is that?

Of course you can always learn to link ideas together, and use one idea to pull another from memory. Memory experts can use this method to pull enormously large amounts from memory. But this method always had a tiny delay, because the ideas are not all in the mind at one time. This suggests that at each moment the mind contains just ten hooks: ten references to other neurons.

Of course you can always learn to link ideas together, and use one idea to pull another from memory. Memory experts can use this method to pull enormously large amounts from memory. But this method always had a tiny delay, because the ideas are not all in the mind at one time. This suggests that at each moment the mind contains just ten hooks: ten references to other neurons.

With training we can remember as many as nine items at once, which suggests an upper limit of maybe nine. Presumably the brain needs an extra slot free (so it is not completely oblivious to the rest of reality in case a tiger attacks), so this suggests that the mind contains about ten variables (changing up to forty times per second).

If the memory expert is distracted, for example by a tiger attack, those hooks are repurposed. This is how digital computer memory works: a series of 1s and 0s are enough to encode every kind of information. That information is constantly shuffled around in working memory, and often compressed so the space normally reserved for one big number can be used for three or four small numbers. Billions of years of evolution mean that brains are vastly more efficient than digital computers, so they must be doing this shuffling and repurposing all the time.

The point of all this? Everything we experience in one fortieth of a second can easily be contained within ten numbers.

With training we can remember as many as nine items at once, which suggests an upper limit of maybe nine. Presumably the brain needs an extra slot free (so it is not completely oblivious to the rest of reality in case a tiger attacks), so this suggests that the mind contains about ten variables (changing up to forty times per second).

If the memory expert is distracted, for example by a tiger attack, those hooks are repurposed. This is how digital computer memory works: a series of 1s and 0s are enough to encode every kind of information. That information is constantly shuffled around in working memory, and often compressed so the space normally reserved for one big number can be used for three or four small numbers. Billions of years of evolution mean that brains are vastly more efficient than digital computers, so they must be doing this shuffling and repurposing all the time.

The point of all this? Everything we experience in one fortieth of a second can easily be contained within ten numbers.

As you can see, it contains the information "4 lots of 5".

As you can see, it contains the information "4 lots of 5".

In other words, 4 waves, each of wavelength 5. So this primitive mind contains primitive waves!

In other words, 4 waves, each of wavelength 5. So this primitive mind contains primitive waves!

(image: Psgs123xyz, via wikipedia, CC0 1.0)

Why does this matter? Because all physics is made of waves. The colour "red" for example is just waves separated by about 700 nanometres. Or in other words 4.3x10^28 planck lengths. A planck length is the fundamental unit of distance in the universe, Being fundamental it is really just a number - whatever we call it only for convenience so we don't mix it up with other numbers. All of physics is like that: just numbers forming waves. The more numbers we have, the more sophisticated ad interesting a point in space might be. We have seen that one number contains information, so is a kind of very primitive mind. Two numbers together contain a very primitive waves, a kind of super-basic knowledge of colour.

Let that idea sink in! Every point in the universe is a mind that knows the concept of colour, or something equivalent.

With three numbers we could add even more richness and detail.

(image: Psgs123xyz, via wikipedia, CC0 1.0)

Why does this matter? Because all physics is made of waves. The colour "red" for example is just waves separated by about 700 nanometres. Or in other words 4.3x10^28 planck lengths. A planck length is the fundamental unit of distance in the universe, Being fundamental it is really just a number - whatever we call it only for convenience so we don't mix it up with other numbers. All of physics is like that: just numbers forming waves. The more numbers we have, the more sophisticated ad interesting a point in space might be. We have seen that one number contains information, so is a kind of very primitive mind. Two numbers together contain a very primitive waves, a kind of super-basic knowledge of colour.

Let that idea sink in! Every point in the universe is a mind that knows the concept of colour, or something equivalent.

With three numbers we could add even more richness and detail.

(image: Alexandre Gondran, via wikipedia, CC4.0)

Every point in space exists in at least four dimensions, when we include time. Imagine how much wave information could be encoded in a four dimensional number. Or even five.

(image: Alexandre Gondran, via wikipedia, CC4.0)

Every point in space exists in at least four dimensions, when we include time. Imagine how much wave information could be encoded in a four dimensional number. Or even five.

(image: Fractal Bargain Bin)

According to String theory, there are ten or even eleven dimensions. That's plenty of space for everything we could possibly think about in one fortieth of a second.

(image: Fractal Bargain Bin)

According to String theory, there are ten or even eleven dimensions. That's plenty of space for everything we could possibly think about in one fortieth of a second.

(image: Fractal Bargain Bin)

Or perhaps the holographic universe theory is correct and there are really just two space dimensions plus time. Remember that while we might think we see colours, but really we see frequencies. It may be that one dimension is the kind of thing we see (colour, shape, happiness, or the belief that we see everything), and the other dimension is which thing we see (which frequency, which shape, how happy, how much we believe that we see it all, etc.). But ten dimensions are easier to visualise, because we think we can visualise ten shapes at once. Even though really we can't.

(image: Fractal Bargain Bin)

Or perhaps the holographic universe theory is correct and there are really just two space dimensions plus time. Remember that while we might think we see colours, but really we see frequencies. It may be that one dimension is the kind of thing we see (colour, shape, happiness, or the belief that we see everything), and the other dimension is which thing we see (which frequency, which shape, how happy, how much we believe that we see it all, etc.). But ten dimensions are easier to visualise, because we think we can visualise ten shapes at once. Even though really we can't.

That is impossible, by definition. So it must be true for the brain as well. This becomes obvious when we think of what consciousness is. Consciousness is where we make the brain's highest level decisions. There can only be one highest level, otherwise we risk disagreement.

That is impossible, by definition. So it must be true for the brain as well. This becomes obvious when we think of what consciousness is. Consciousness is where we make the brain's highest level decisions. There can only be one highest level, otherwise we risk disagreement.

This has to be true right down to the subatomic level. Therefore consciousness must be a point in space. It cannot be a system of many points. (Invoking Heisenberg's uncertainty principle does not help: the principle proves there is uncertainty, not logical contradictions.)

This has to be true right down to the subatomic level. Therefore consciousness must be a point in space. It cannot be a system of many points. (Invoking Heisenberg's uncertainty principle does not help: the principle proves there is uncertainty, not logical contradictions.)

(image copyright K C Green, Okayed for social media - does this count?)

(image copyright K C Green, Okayed for social media - does this count?)